‘Games: Agency as Art’ — A Behavioral Scientist’s Book Review

On any given day, I might procrastinate eating for a few hours because the effort of toasting a frozen Eggo waffle seems like a bit too much. Yet when it comes to games, I choose to make my life more difficult. I relish the arbitrary rule of dribbling a basketball even though the game would be easier without that constraint. I prefer opponents who will challenge me in Bridge, and dislike the “Easy” setting on most video games. I also resist the urge to cheat even if it would mean victory. And when I lose, so long as the challenge was fun and intriguing, I will likely want to play again.

Games are a complete inversion of typical motivation and seem exempt from the most powerful rule in Behavioral Science; Richard Thaler’s advice that “If you want to get somebody to do something, make it easy.”

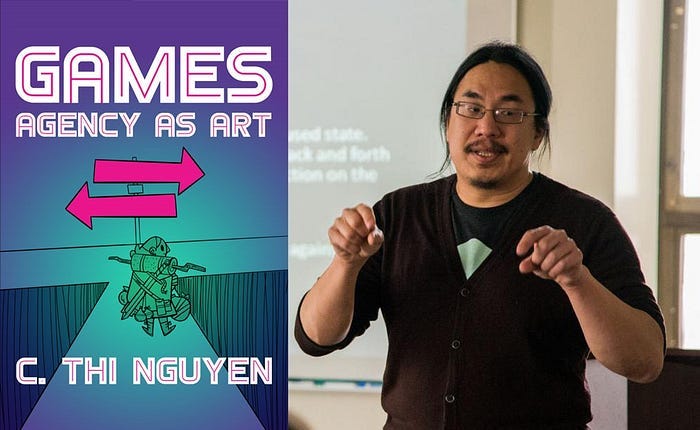

In games, the consequences of the struggle are not the point; rather the struggle is the point. Or so argues Thi Nguyen in his book Games: Agency as Art. A book which gave me much to reflect on as a professional behavioral scientist. It is simultaneously a love letter to the potential of games to change behavior, and also a screed against gamification.

In games, he argues, the struggle is designed in such a way that it can be interesting, fun, or even beautiful. When you play a game, you play for the experience the struggle brings you. The struggle is not a means to an end, but is itself the end. We want the struggle.

This isn’t to say that people don’t care about status, social cohesion, or any number of other functions that a game might serve. Nor is anyone likely to be indifferent to winning. Personally, I want nothing more than to take a baseball bat and slam my nephew right off the stage every time he brags about how he is better at Super Smash Bros.

Instead, what I am saying — and what Nguyen argues in his book — is that the challenge itself has value independent of these other consequences. The constraints, goals, and abilities of a game may seem arbitrary, but those elements come together to ensure the struggle has a unique aesthetic quality that is worth experiencing for its own sake. Games turn struggle into art.

When you play to win, Nguyen calls it Achievement Play. But Striving Play — playing for the sake of the experience — is the hero of this story. In Striving Play, there is a certain psychological distance from winning. In games, it’s not that winning is a means to some goal, but rather, it’s that adopting-the-goal-of-winning is a means to an end. There is a paradox where one must simultaneously care about winning while still maintaining distance from actually caring about winning.

This is perhaps most clear in games where losing is part of the fun, though it’s important to note that the principle is broad enough to apply to all games. Consider Twister where falling down and therefore failing is what makes the game so fun. Nevertheless, if you fall down intentionally, the fun will be stolen from you. To truly experience Twister, you must adopt the goal of winning even while winning is not the point. Or if like me you haven’t played Twister in 20 years, consider drinking games. Who wants to be so good at a drinking game that they never have to drink (except those of us who don’t drink)? In such games, losing might be part of what makes the game fun even while you still have to try to win in order to have the full experience.

Again, in a total inversion of typical motivation, we adopt-the-goal-of-winning as a means to engage in a struggle. As Nguyen says, “In most of life, we justify our goals in terms of their intrinsic value or the valuable things that will follow from them. In games, we justify our goals by showing what kind of activity they will inspire.”

In Striving Play, losing can still hurt, and winning is still usually fun, but the true purpose of Striving Play is the aesthetic experience one has while struggling to play well. This idea forms the heart of the book and sets up what I consider three of the most critical takeaways from the book for behavioral scientists.

Agency as Art

Agency is an awkward word which I am loath to use, but feel I must. Agency means active and intentional action such as thinking, deciding, doing, or planning. Non-agentic actions would be things we do passively or reflexively such as when the doctor hits your knee with that little mallet and your leg kicks — you never make the choice to kick and so that is not agency.

Nguyen builds on the concept of agency by talking about agentic modes — another awkward term which is perhaps related to “mindsets” or “ways of being.” For example, when writing a research paper, you must engage in various agentic modes: research mode, creative mode, rigorous mode, communicative mode, and a nit-picky proofreading mode. All of these modes require different capabilities, and each has a different qualitative experience to them. Being creative feels different than proofreading, which feels different than thinking rigorously about an argument you are writing. You probably have a preference for which of these modes you would rather engage in.

Nguyen argues that just as a painting captures a sunset or a book captures falling in love, games capture the experience of agentic modes.

Games can still have other aesthetic qualities, such as beautiful imagery, a compelling story, or a great soundtrack. But in addition, games have a medium unique to themselves; human agency. Here is how Nguyen describes this in the book:

“John Dewey suggested that many of the arts are crystallizations of ordinary human experience. Fiction is the crystallization of telling people about what happened; visual arts are the crystallization of looking around and seeing; music is the crystallization of listening. Games, I claim, are the crystallization of practicality. Aesthetic experiences of action are natural and occur outside of games all the time. Fixing a broken car engine, figuring out a math proof, managing a corporation, even getting into a bar fight — each can have its own particular interest and beauty. These include the satisfaction of finding an elegant solution to an administrative problem, of dodging perfectly around an unexpected obstacle. These experiences are wonderful — but in the wild, they are far too rare. Games can concentrate those experiences. When we design games, we can sculpt the shape of the activity to make beautiful action more likely. And games can intensify and refine those aesthetic qualities, just as a painting can intensify and refine the aesthetic qualities we find in the natural sights and sounds of the world.”

Nguyen asks us to consider chess as an example.

“Doing math, philosophy, and the like, can give rise to aesthetic experiences of calculation, puzzle solving, and glorious leaps of the mind. Chess takes that sort of activity and crystallizes it. Chess offers us a shaped activity particularly fecund in aesthetically rich experiences of the intellect.”

Interestingly, rather than some object having an aesthetic quality, it is your own agency that evokes emotions of beauty, harmony, tragedy, hilarity, etc. Nguyen calls it Process Art as opposed to Object Art. Other examples of Process Art might include cooking, dancing, doing math, or even making art. The outputs of these processes, such as a well-prepared meal, may also have their own beauty. But here we are interested in the aesthetic experience of the process itself, the aesthetic experience of a particular agency, or agentic mode.

My own experience of this sort of crystallization is with machine learning.

There is a particular pleasure in figuring out how to arrange data to get the results you care about. You have all these constraints and challenges you must overcome such as selection effects, dirty data, and the omnipresent lack-of-data-you-actually-care-about. And it was fun. The process of figuring out how to turn data into something usable was a big, exciting puzzle.

The agentic mode of data manipulation was so strong it sometimes even invaded my dreams in my own perverse version of the Tetris Effect. Dreaming of data tables might sound nightmarish to some. But occasionally I would wake up in the middle of the night convinced I had solved some big problem I had been working on, and it felt like watching one of those videos on r/oddlysatisfying where everything lines up perfectly and falls into place. However, there was a sense of finality to these dreams that a gif can never achieve.

And then, I left the world of machine learning to pursue something I was more passionate about — Behavioral Science, and I lost the aesthetic experience that I had grown accustomed to. While it was the right choice, I began to miss the challenge.

But a few years ago, I stumbled across a video of this British guy having a positively sublime experience doing a Sudoku — going so far as describing the particular puzzle as the “universe singing.” He was so passionate and in love with the game that I knew I had to give Sudoku another try after years of forgetting the game even existed. And lo and behold, I enjoyed it — especially Cage Sudoku, which has an additional constraint beyond normal Sudoku.

After a couple of weeks of playing the game, I realized it was the same aesthetic experience as building a machine learning model. Not entirely the same, but there was something about thinking through the constraints of a Sudoku that felt like thinking through the constraints of the data when building a model. A kind of Cognitive Fidelity that wasn’t immediately apparent, but which grew as I played more. In both machine learning and Sudoku, you are trying to control for all the possibilities to ensure only one possible solution, or interpretation, remains. Now if people ask me what data science is like, I tell them it is a bit like Sudoku — you play around with constraints until everything lines up and you are left with only one possible solution.

Nguyen would say that Sudoku is the crystallization of a specific agency that I will call reasoning by constraints. Other games crystallize other types of agency, such as chess capturing the agency of calculation and leaps of logic, the game Sign crystallizing the agency of stabilizing meaning, and Monopoly crystallizing profit maximization.

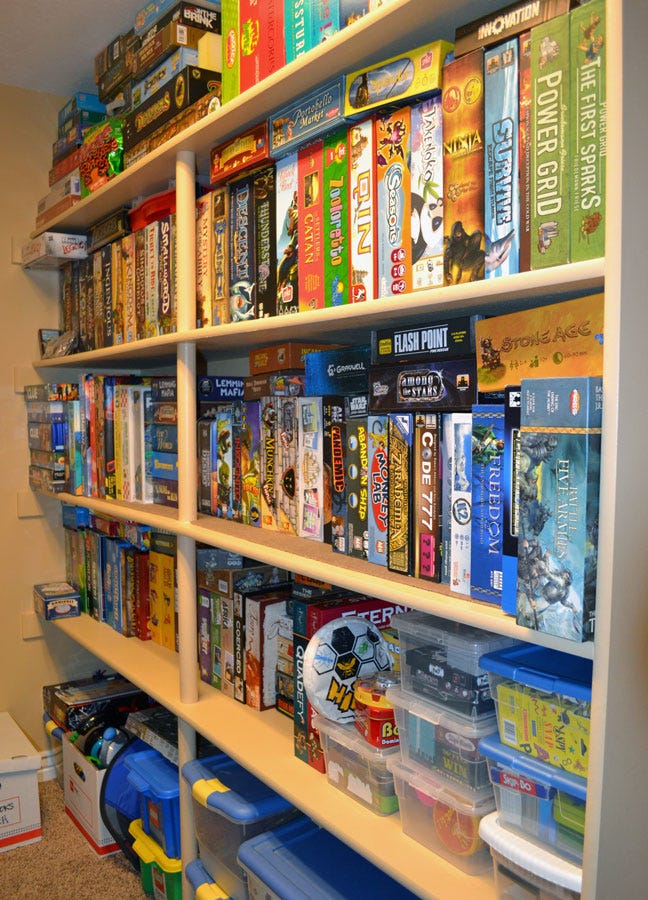

Together, “A collection of games can, then, constitute a library of agencies,” Nguyen says. Recorded bits of human experience ready to be taken up. Not an escape from reality, but rather each game distilling a specific aspect of reality. “One game might be focused on high-speed reflexes, another on calculative look ahead, or on diplomacy and bargaining, or on manipulating alliances and shared incentives.”

Games “are a method for inscribing forms of agency into artifactual vessels: for recording them, preserving them, and passing them around.” A way to communicate agencies from one human to another. Two people who have never met, separated by geography, time, and language barriers, can play the same Sudoku puzzle and have the same agentic experience. And I can share with you, at least in part, what it feels like to do data science regardless of whether you know the first thing about Neural Nets.

Other art mediums can portray other aspects of data science, such as a beautiful chart which shows the complexity of a social network. But only games can crystallize the experience of doing data science because only games use your own agency as a medium.

Leveling Up Your Agency

The idea that games are a medium through which we can share agencies brings up an intriguing possibility: can we use games to expand our repertoire of skills?

Nguyen thinks so. “Games can experientially immerse a player in an alternative agency, making that mode of agency more available to the player elsewhere in life. Games can help to build a broader menu of possible ways of being an agent.” This can, in turn, expand our freedom and autonomy in what is a more realistic version of downloading Kung Fu directly into the brain as in The Matrix.

Here are three ways that games might expand our agentic abilities.

For one, a game may help us grow familiar with an agentic mode that was previously strange to us.

For example, for someone who is clumsy and unfamiliar with graceful movement, taking up gymnastics can teach them what it feels like to move gracefully through the world. Or perhaps someone is naïve and overly trusting, in which case playing Poker may help them develop their lie-detection skills. If someone has never seriously engaged in these agentic modes before, then these activities may help them to know how it feels to do so, which will allow them to more easily embody those ways of being outside of the game.

Second, shifting between games may enable us to be more fluid in our ability to shift between ways of engaging with the world.

A friend of mine knows quite well the value of such fluidity. Before playing Poker, he likes to watch math videos to get him into a more calculative agentic mode. Others may know how difficult the transition between work and home life can be. It is not uncommon for someone to stay in the car for a few minutes before coming into the house after work because they need a few minutes to decompress and prepare for a different way of engaging with the world — a transition which has been upset in our current world of remote work.

Such shifts in agentic modes are common when one plays games. In a video game, you might be slaying a monster one moment, exploring a beautiful mountain vista the next, and searching for mushrooms right after that. The ability to shift between agentic modes may be a valuable trait worth pursuing for those of us who may dig in our heels a bit too long.

Lastly, a game may teach us to enjoy an agentic mode we hadn’t previously. This aspect is perhaps the most interesting to me, and so it is where I will focus.

In arguing that games can help us enjoy something we previously hadn’t, Nguyen is not referring to gamification, which is something he is concerned about — more on that in the next section. Instead, he argues that in embodying a specific agentic mode, we can learn to appreciate the aesthetic quality of that mode.

Consider my earlier example of machine learning and Sudoku. I didn’t particularly enjoy Sudoku as a kid but learned to love it as an adult because it offered a similar aesthetic experience to Data Science. Now just reverse the order of those events. Could someone learn to love Data Science by playing Sudoku?

Nguyen’s personal example is that he didn’t start out as a very good philosopher. His advisor said he was great with questions but didn’t have the temperament to sit down and think logically through a problem. But then Nguyen started playing chess which showed him that sitting down and thinking logically through a problem could actually be fun and have it’s own type of pleasure. Having realized that such thinking could be fun, Nguyen started to develop a knack for it.

Nguyen argues that such transformations can happen because games are right-sized for our abilities. In most of life, our challenges are beyond us. Too complicated, too complex, too vague, and too different from what we are used to, and so not enjoyable. No one enjoys being bad at something.

But games are designed to fit our skills and abilities. “In games, the problems can be right-sized for our capacities; our in-game selves can be right-sized for the problems; and the arrangement of self and world can make solving the problems pleasurable, satisfying, interesting, and beautiful.” And by starting with these “right-sized” challenges, we can learn to enjoy an agentic mode that we had previously only engaged in with poor results.

Here is another way to think about it: how can someone learn to love the struggle of exercise if they never learn to love the struggle of a sport where they perform well? How can they learn to love the struggle of a good intellectual challenge if they never meet a challenge that is the perfect intellectual size to struggle with and solve? Perhaps games are one key, among many, to conditioning ourselves to enjoy agentic modes we had previously found boring or difficult, and as a result, to expand our ability into realms of challenge we had previously found daunting or tedious

Let’s rein this back for a second. I don’t think games are the key to permanently solving the intention-action gap, and Nguyen doesn’t either. And every behavioral scientist worth their salt knows that making something fun and enjoyable is a great strategy, so that isn’t a new insight.

But typically we think of making-behavior-fun as a strategy that should occur during the behavior by adding various elements such as points or badges (in the most basic forms of gamification). Instead, Nguyen invites us to consider the importance of learning to enjoy the struggle for its own sake, and the roles of games in helping us to overcome the gap between what we want to enjoy and actually enjoying it.

For example, the fact that I want to be a writer does not mean I want to write. The gap between wanting-to-be and wanting-to-do is quite large. But perhaps games are a bridge between the two. If we can crystallize writing and its associated agentic modes, perhaps I can learn to better appreciate the satisfaction that comes from saying something well. And perhaps that will draw me to write even when I could be doing other things. Not because I’ve gamified writing, but because the struggle of saying something well is pleasingly difficult. A struggle that I want to engage in for its own sake.

Just as Nguyen learned to love philosophy through chess, perhaps through games we can learn to love the aesthetic experience of a certain form of agency — the agency of the person we want to become. And if this is true, it is worth considering whether our current methods, such as making-things-easier and gamification, may be good for changing behavior, but counterproductive for changing people.

The idea that aesthetic experiences can shift our values is not a claim unique to games. Art has long been noted for its ability to influence our values. From popular culture, to religion, to government propaganda, art is brimming with the ability to focus and change values. But a game’s ability to expand our capabilities by influencing what we enjoy seems a particularly interesting approach for someone like me who is interested in motivation and behavior change.

How to actually apply this is still an open mystery. No one argues that reading Dostoyevsky once will make you a good person, and Nguyen isn’t arguing that playing Settlers of Catan will make you a good steward of resources. At the end of the day, this is a book of philosophy, not science or self-improvement. Nguyen merely wants to claim that though a game seems to impose arbitrary constraints, goals, and abilities, these may in fact serve the important function of expanding our agency. Indeed, maybe that is their evolutionary and developmental purpose. I agree and hope that his work inspires others to put his claim to the test.

Value Capture

Anything that can shift our values has potential for good and ill — whether religion, propaganda, or even games.

Nguyen’s concern isn’t that Call of Duty will turn us into mass shooters. Nor is it about young men spending too many hours in their parent’s basement playing World of Warcraft. Rather, the concern is that our fundamental values will be shifted and over-simplified in a process he calls Value Capture.

This process is closely related to another idea called Goodhart’s Law, an important idea in it’s own right.

Goodhart’s Law states that “once a metric becomes a target, it ceases to be a good metric”. As an example, imagine a teacher who feels forced to ‘teach to the test’ because test scores are the metric by which they will be judged. Initially, test scores might be a good metric for quantifying student success, and therefore teacher success.

But as the teacher feels mounting pressure to improve test scores, the teacher shifts the focus of their lessons away from ensuring the children are learning and towards ensuring the children will perform well on the test. The teacher probably knows the metric is wrong-headed, and is angry that their performance is rated on a simple metric that doesn’t capture how well they are doing their job. But they must teach to the test anyways, and by focusing on the metric, the correlation between test scores and student learning de-correlate because the teacher is forced to exploit the gap between the two.

The key difference between this example of Goodhart’s Law and Nguyen’s concern is that once the metric is taken away, the teacher will sigh a breath of relief and return to how they had originally taught. The shift in focus only endured for as long as the metric was enforced. Not so in Value Capture.

Imagine a different scenario where a school creates a competition to see which classroom can get the highest test scores. In this scenario, the teacher buys into the game and is excited by the metric. They do their best to optimize their students for test-taking, and increasing test scores becomes not just a challenge at work, but instead an exciting pastime.

In this scenario, even once the competition and metric are taken away, the teacher may develop a taste for it and may be excited at the prospect of finding new ways to increase test scores. Worst of all, maybe they enjoy it so much that they want to apply that same maximization mindset to other areas of their life. Number of steps walked, number of hours worked, number of sex partners had. Maximize everything.

Nguyen concludes that “We shouldn’t worry about games creating serial killers, we should worry about them creating Wall Street bankers.” People for whom finance is just a game to win, not a serious endeavor with lives at stake.

If Nguyen is right, aiming for a metric is always dangerous because metrics are a type of incentive system. There’s always the danger of not just missing the true target by aiming at an imperfect proxy (Goodhart’s Law). But also a larger danger of changing our perception of what the true target even is as we learn to enjoy pursuing the proxy (Value Capture) and the accompanying agentic mode.

Nguyen’s favorite example is Twitter, which, he argues, gamifies communication. Maybe someone joins the platform to engage with people, change minds, or stay current on the latest news. But once they are on there, the platform embeds them in a game of its own design by giving them a point system of likes, re-tweets, and followers. These metrics are of course correlated with their goals, so they play the Twitter game. But after a while, they become less interested in changing minds than in posting memes and dunking on their most hated politicians because that gets them the most likes and retweets.

As they pursue the metrics, the metrics de-correlate from their initial values (Goodhart’s Law), but even worse, they start to enjoy pursuing the metrics more than they care about engaging with people, changing minds, or staying current on the latest news (Value Capture). This is something Jack Dorsey has even commented on when he says he wished he had hired Behavioral Economists and Game Theorists to better understand the incentive system he and his team were creating. The seemingly small choice of including numbers at the bottom of every tweet has had an outsized impact on the very nature of what Twitter is, and the way our discourse has developed.

He who controls the point system controls you, argues Nguyen. The nuanced values we develop throughout your life, such as the desire to connect with others, find the truth, and contribute to society, are lost to simplified metrics as social media companies gamify communication, academia gamifies knowledge production, and workplaces gamify production. At the end of the day, how can we even be our own person when large organizations determine which metrics we should care about?

Such quantification wouldn’t be a problem if we could match our metrics to our goals exactly. But here is a deep truth: that which matters most is the least measurable. We can try to operationalize things like love, goodness, and beauty. But our metric will always be subtly off from what we care about, and the gap between the metric and the value always grows as the metric is pursued.

Perhaps one of the biggest takeaways from the book for behavioral scientists is around Value Capture. We shouldn’t think of metrics, incentives, and point systems as providing targets for people to aim at. But instead we should think of them as Skinnerian rewards which change who we are as people by changing how we like to engage with the world. A power that many corporations now wield.

Or at least, that is a fear that has begun to grow in my mind. To tamper with these powers is a responsibility that we perhaps haven’t yet fully understood. The impact of our interventions may continue long after someone closes the app.

Conclusion

No book review can truly do justice to all of the fascinating lines of thought in a book like this. Suffice it to say there is more I wish I could have written about. Yes, there are parts I had to slog through (Striving Play is real, move on already), but for the most part the book captured me in a way that few other books ever have. Two years later and I still think it is the best non-fiction book I’ve read since graduating college.

Nguyen’s prose is easy to follow and not too academic — and when he is academic he manages to make things clear anyways. Part of what makes the book so fun is something I skipped entirely for this review to keep the length down: Nguyen himself is an encyclopedia of board games. One wonders where he finds the time to play so many games while fulfilling his other responsibilities. It is good that he found a wife who seems as obsessed with games as he is — as far as I can tell, their relationship seems to consist entirely of competition.

The criticisms of the book that I do have are all a bit unfair. He wrote a book on the philosophy of games, and I desperately wanted him to write a book on psychology. A couple of chapters on the psychology of aesthetic experiences, and the impact of art on values would have been welcome. Not to mention a couple of studies testing out the ideas he puts forward.

But at the end of the day, this is a book about the philosophy of games. The questions and criticisms Nguyen focused on have set the stage, and it is now up to others to expand on and test his ideas. Perhaps, if I may bury a seed into your mind, even by people who read this book review.

One thing this book has made me reflect on is how my choice of games has either influenced or predicted the direction of my career. My research interest in expert intuition seems in many ways to match the types of games I like to play. And my favorite part of a project, turning a complex problem into a framework and actionable strategy, has a similar type of satisfaction as Sudoku.

This has caused me to reflect on the role of games in education and aptitude testing. We have an existing library of human agencies in the form of games. What can they tell us about who we are, what kind of ways we like to engage with the world, what kind of careers we might enjoy? Could they also help us to enjoy aspects of our career we find tedious or difficult? These questions fascinate me. I wonder how much of my career path was determined in the moment my mom brought home a brand new PlayStation and Crash Bandicoot.

If you do not have time for the book, I recommend listening to some of the podcasts Thi Nguyen has been on. The three I have heard (Ezra Klein, Mindscape, and Complexity) have all been excellent dives into the nuances and dangers of metrics and quantification and the (false) moral clarity they provide. Nguyen doesn’t offer much support or nuance on the benefits of quantification, so how to handle those trade-offs is left to the reader (or listener). Still, his are important and interesting criticisms to add to the list when thinking about metrics.

Overall, Games: Agency as Art is an excellent read that has changed my perspective and given me a new way of thinking and approaching many topics, including things not mentioned in this review. It even impacted a project on Choice Overload I worked on by getting me to focus on the aesthetic experience of choice, as opposed to the number of options. All in all, I would love to see more engagement with these ideas in the Behavioral Science community, and so recommend the book to anyone who can get through a 5000-word book review.