Occam’s Razor isn’t a metaphysical truth, it’s just part of science

Or at least, we scientists don't need to concern ourselves with the metaphysics

I recently read an article arguing against Occam's Razor. Here’s an excerpt.

Occam’s razor is not a fact or even a theory. It’s a metaphysical principle: an idea held independently of empirical evidence. (Think “God is love” or “beauty is truth.”) But unless we are prepared to make assumptions about God and nature, there is no good reason that we should prefer a simpler explanation to a complex one. Moreover, in human affairs things are more often than not complex. Human motivations are typically multiple. People can be good and bad at the same time, selfish and selfless, depending on circumstances. The shelves of ethicists are filled with books pondering why good people do bad things, and their answers are rarely short and sweet.

While I’m usually the person talking about complexity, context, and the oversimplifications of scientific models, I don’t find myself sympathetic to this argument. Yes, reality is complex, and I would love for Complexity Theory to be taken more seriously. But, Occam's Razor isn’t a constraint that prevents us from proposing complex theories, nor is it a claim about the nature of reality. Rather, I think of it as a starting point and something that is just inherent to science.

I don’t claim to be a philosopher of science, but I did recently have a very long flight to Florida which gave me time to collect my thoughts. Surely that is enough time to claim expertise and put my opinions on the internet.

Constraining the search space

One semi-common technique in science is eliminative inference—where we consider various hypotheses and eliminate them one by one. However, because the set of possible hypotheses is infinite, we cannot actually eliminate them all. This is where Occam's Razor becomes useful: it helps us constrain the initial search space to something manageable.

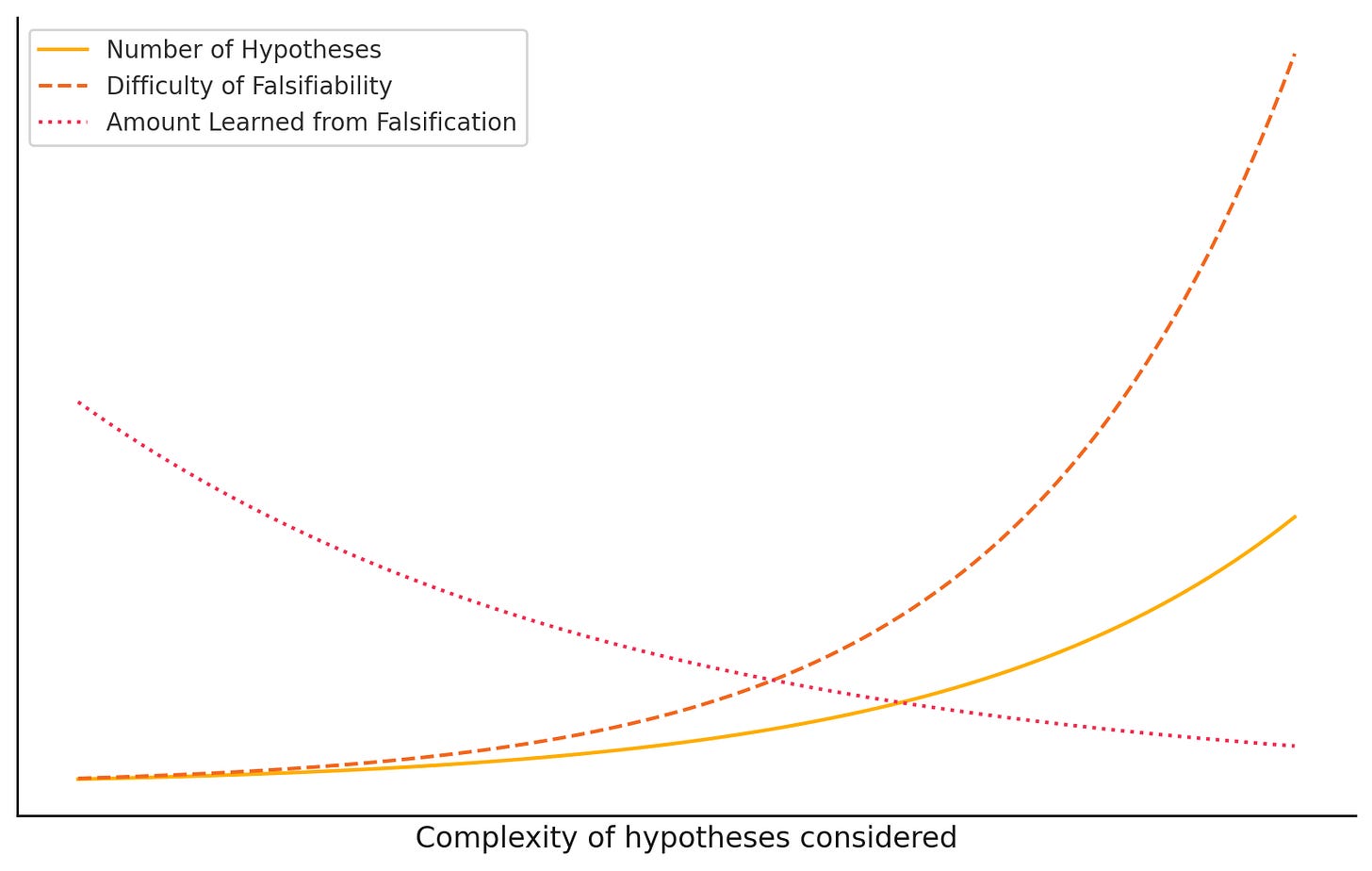

By favoring simpler hypotheses, we limit the number of explanations we have to consider as the number of hypotheses which explain a phenomena increases exponentially with increasing complexity. This doesn’t mean that simple explanations are more likely to be true or that we’ll stop with simple hypotheses. It’s just an efficient way to start.

For example, in a murder investigation, we begin by considering simpler motives, like jealousy or revenge, rather than jumping straight into conspiracy theories. Not because conspiracies never happen, but because if the motive is simple, we can find it quickly, and if it’s a conspiracy, then the probability that we identify the correct conspiracy early on is very small anyways because the number of conspiracy theories which could explain the murder is so vast.

Not only that, but complex hypotheses are harder to falsify. The more variables a hypothesis introduces, the more difficult it becomes to control for all the variables. With each additional layer of complexity, we increase the amount of data required and complicate the process of eliminating false explanations. This means, as a purely pragmatic matter, it is almost never useful to propose a hypothesis that is vastly more complex than the least complex hypothesis which still hasn't been falsified.

This increased difficulty of falsifiability means we also learn little from testing such theories, whereas testing simpler explanations is often very informative. For example, in the murder investigation, if jealousy isn’t the motive, the process of falsifying that hypothesis (such as by talking with the husband and getting his alibi) might reveal new information that points us toward a political or conspiracy motive, giving us a better direction for which complex hypothesis to be testing next. Whereas falsifying that a cabal of elites were somehow involved is very unlikely to be very informative and tell us where next to search.

This means that, again as a purely practical matter, it is better to start with simple hypotheses as they are fewer, easier to test, and often more informative than the falsifications of complex hypotheses.

Scientific progress

Philosopher Thomas Kuhn famously distinguished between ordinary science and revolutionary science. In ordinary science, researchers often add complexity to existing models—appending caveats, exceptions, and nuances. In psychology, this looks like appending “it depends” statements to every situation in which a theory or finding falls short.

Revolutionary science, on the other hand, occurs when researchers uncover hidden simplicity. When we replace all those “it depends” caveats with a simple formulation that accounts for even more than the original theory ever explained (even with its plethora of caveats and exceptions), we advance scientific understanding.

Occam’s Razor nudges us toward this kind of revolutionary science. It encourages us to be dissatisfied with complex models filled with exceptions, and to search for simpler, more elegant solutions that can explain even more.

This may seem like I’m begging the question. Why prefer revolutionary science if simpler answers are not more likely to be true?

Scientific revolutions are progress, I believe, and the reason is very simple; pre-revolutionary theories are failing to do their job. All those caveats, exceptions and “it depends” we gather overtime need an explanation which the theory isn't providing. They are an indication we need to go back to square one and once again start proposing simple hypotheses which explain all the evidence.

The purpose of scientific models

Occam’s Razor works well in science because it aligns with the very purpose of science. I’m not going to wring my hands about this, and if you disagree with my definition we can fight about it in the comments. But I believe the purpose of science is to create human-intelligible models that effectively explain phenomena.

There are two reasons why simpler models succeed. First, they are more intelligible. A simpler model is easier to understand and work with. Take the example of fixing a wobbly table. It’s far more manageable to focus on one leg than to address all four at once. Is it metaphysically correct that the table has one leg that is too short and the other three are fine? Of course not. Nor is it metaphysically correct that the 3 legs are wrong. But simplified models help us focus on manageable aspects of a problem by clarifying causes and possible counterfactuals. Science similarly simplifies the world. Indeed that is it’s very purpose.

Second, simpler models are almost always more generalizable because of the inherent trade-off between specificity and generalizability. Reality is complex, and you can always get more specific by adding complexity. However, when we zoom out to explain broader phenomena, we naturally arrive at simpler models. For instance, it’s easier to explain the causes of prevailing wind patterns than it is to explain the cause of an individual gust of wind. The former problem actually requires far less complexity than the latter.

In this sense, Occam's Razor isn't declaring that the world is simple—instead it makes it simple enough for us to work with. The complexity is still there, but the purpose of science is to abstract it into something we can manage. Science, by its very nature, hides complexity to give us useful and intelligible models

But why prefer the simple hypothesis?

“But Jared,” I can hear you say, “given a choice between two hypotheses, one simple and one complex, why do we prefer the simple one? Why does it seem like the simpler hypothesis is more often correct?”

You are right to call me out on this. I haven't actually provided an answer. The straightforward murder is more likely than a conspiracy. The more parsimonious “the car battery died” is more likely to be true than “multiple systems have all failed.” The simple hypothesis that the dinosaurs were killed by an asteroid is more plausible than the idea that both an asteroid hit and volcanic eruptions happened covering the earth in volcanic ash.

Individually, each of these seem trivial to explain. Conspiracies are hard to form, and harder to maintain and so commit less murders than jealous husbands. Cars are designed modularly meaning failures end up isolated. Two random events happening simultaneously are less likely to happen than one by itself. In so far as Occam's Razor actually describes the world, it does so in trivial ways that do not require us to understand the fundamental building blocks of the universe.

But is there a collective explanation? Perhaps? There could be some metaphysical truth underlying the three trivial explanations. Occam's Razor demands I look for one after all, and it seems not implausible it exists—perhaps something to do with how modular the universe is, or about how humans conceptualize the universe as modular. Maybe I shouldn’t be so quick to dismiss the metaphysical possibility!

But the thing is that we don’t need the metaphysical explanation in order to understand the success of Occam’s Razor. Instead, we only need to understand the purpose of science, and how it works. We can leave the metaphysics to the philosophers while we go about our business.