Ranking Behavioral Science Frameworks

A couple months ago, I decided to do a series of posts on LinkedIn where I reviewed various behavioral science frameworks and put them into a tier list. The series got quite a bit of engagement from other behavioral scientists who sometimes agreed, sometimes disagreed, and sometimes gave pretty serious pushback on the entire effort of ranking frameworks.

I have decided to re-publish those posts on my Substack, along with a couple of updates and many links.

The biggest difference is that I've changed the ranking of two frameworks (Opposing Forces and the Fogg Behavior Model). The latter I have actually completely re-written as my opinion has changed significantly since writing that post. If you saw my original post on that model (which I called BMAP), please see my updated rankings. I do not endorse my original post on that model.

I have also gotten rid of the middle tier where I had originally put these two models.

In a follow-up article I will do a review of what I learned in doing this series (which you can now find here). But here I will share my original posts and their updated rankings, and a link to the original post so you can see the comments, which were often very informative. Also note that this post isn’t meant to be a full explanation of the model. For more in depth analyses, I recommend Decision Lab’s Reference Guide or Habit Weekly’s guide (for pro subscribers only), which both give more background and detail on many frameworks.

For the final ranking of all the models, scroll to the bottom of this post.

Frameworks, Models, and Theories, oh my!

A few weeks ago, Samuel Salzer (founder of Habit Weekly, co-host of the Behavioral Design Podcast, and one of my co-founders at Nuance Behavior) and I ranked Behavioral Science frameworks for a boot camp he was running. But an hour wasn’t enough to dig into the nitty-gritty—and that’s where the real fun begins. So I've decided to give it another shot.

Over the coming weeks, I’ll be evaluating and ranking behavior change frameworks for a #FrameworkTierList series.

What exactly is a behavior change framework?

Frameworks aren't paradigms, theories, or models. Behavioral Science is a paradigm, Loss Aversion is a theory, and the equation describing it is a model.

Frameworks, on the other hand, are pragmatic tools for organizing, evaluating, and applying ideas to solve problems—in our case, behavior change. They are primarily pragmatic rather than scientific in nature. In this series, I'll review frameworks like COM-B, EAST, and 10 Conditions for Change, among others.

How will I rank them?

Context matters, and there is always some context for which a (scientifically informed) framework will be S-Tier. But for this, I will keep to a clearly defined criterion: usability for organizing a behavior change project. Hopefully this criteria will keep me honest and prevent me from gushing over frameworks which I find personally engaging, but which I wouldn't actually use for a project.

EAST

Kicking off the #FrameworkTierist series, we’re starting with EAST—one of the most popular frameworks when talking about behavior change.

What is EAST

EAST stands for Easy, Attractive, Social, and Timely—four principles to consider when trying to influence behavior. Developed by the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT), it was designed to simplify an earlier, more complex framework (MINDSPACE) that was a tad too long to be considered easy.

Strengths

The best thing about EAST is that it is so easy to remember. While I don't believe I’ve ever used it as the core framework for an entire project, I nevertheless find myself thinking through its principles all the time. If you asked me right now how I would approach a specific problem, my mind would default to thinking E-A-S-T.

Weaknesses

All frameworks trade off simplicity with comprehensiveness, and EAST errs towards simplicity. This makes it great for quick thinking, but results in the framework feeling too general and vague, and also lacking in comprehensiveness. While each letter represents an important principle, I can’t help but feel I need another framework to balance it out to make sure I am not missing anything important.

Final ranking

My criterion for this series is “usability for organizing a behavior change project.” Based on that, EAST performs pretty well. Frameworks are meant to be foundational, and EAST is great for establishing a foundation to build upon. However, its generality and lack of depth means I would rarely actually use it as an organizing framework for a project. As Elina Halonen put it last week when I announced this series, EAST and its predecessor MINDSPACE aren't even really trying to be organizing frameworks. They “are mnemonics, more of a checklist than actual frameworks.” This nudges EAST out of S-Tier in our criteria. While it excels at what it is trying to do, it likely shouldn’t be your organizing framework.

A-Tier, it is.

Update: Between my original post and writing this Substack, Michael Hallsworth has released an updated version of EAST. Check it out here.

Behavioral Drivers Model

Every framework trades off simplicity and complexity, and in this #FrameworkTierList entry, we’re fully on the side of complexity with the Behavioral Drivers Model.

What is the Behavioral Drivers Model (BDM)

The BDM was developed by Vincent Petit at UNICEF when he grew frustrated with all the different frameworks which overlapped. The result is one of the most detailed behavior change frameworks available, incorporating elements from just about every other framework out there.

Strengths

By incorporating so many elements from so many frameworks, BDM ends up being an excellent reference tool to ensure you’re not overlooking any key behavior change drivers. It covers just about everything one could want.

Weaknesses

That strength is also its weakness. The sheer volume of information packed into the BDM makes it difficult to reference quickly. It’s a lot to manage, and when you need to prioritize actions or communicate with stakeholders, its complexity can be overwhelming.

Final ranking

How do you rank a model that is so comprehensive that you are wowed by it, but which you never use precisely because it is so comprehensive? As I've said in the past, every scientific framework has a context for which it is S-Tier. And if this ranking were based purely on the merits of the framework itself, the BDM would be an S-Tier. Vincent did an excellent job with the framework, and I wish I had more excuses to use it. But I am looking for something that can serve as a central organizing framework to organize ideas in a way that helps to diagnose, solve, communicate, and align stakeholders. The BDM struggles with this because it is too vast, too comprehensive, too unwieldy for anyone who is not a behavioral scientist and who isn't willing to spend time getting to really understand its depths. For these reasons, you wouldn’t use it for organizing a project.

It seems unfair to give a low ranking to such a great framework. But BDM isn't meant to be a central organizing framework for a project, which is my criterion in this series. Final verdict: B-Tier.

COM-B

If EAST is too simple and the Behavioral Drivers Model is too complicated, this framework falls right in the Goldilocks zone. This week, I’m ranking the COM-B framework.

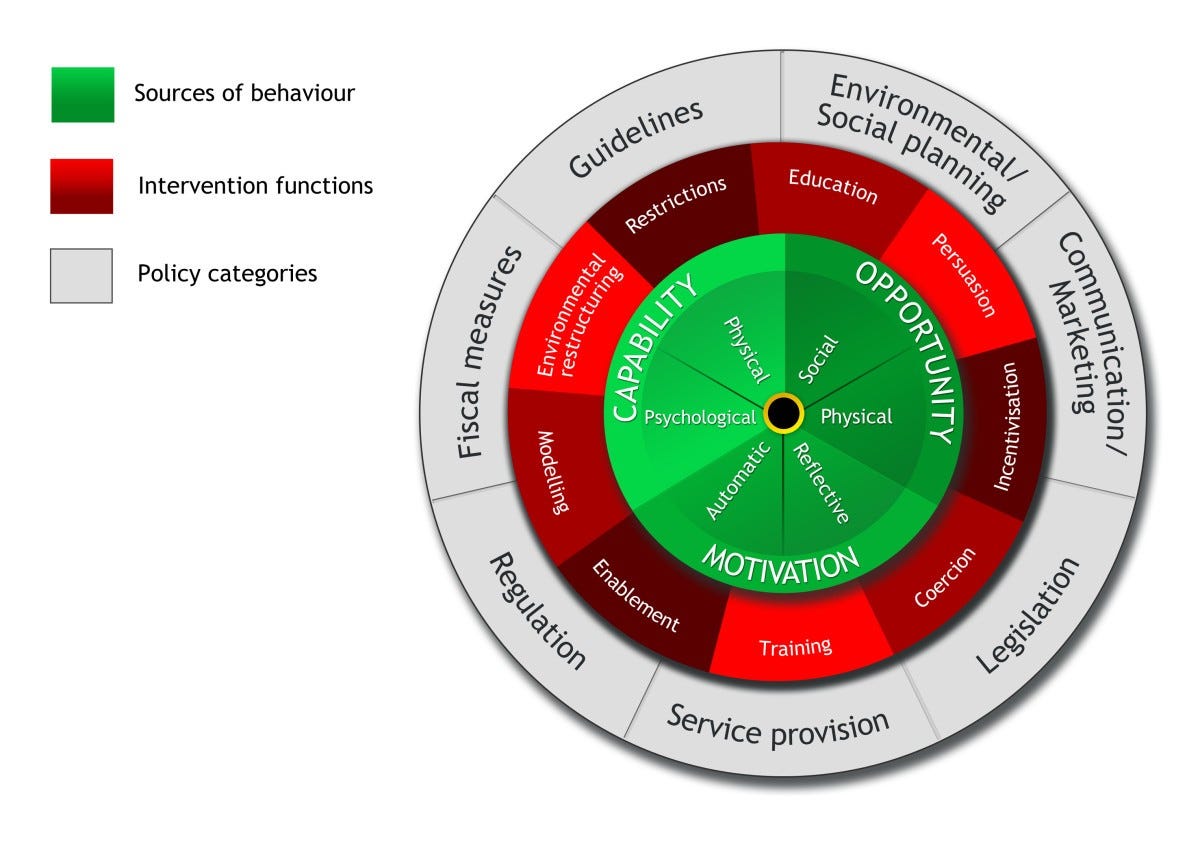

What is COM-B

COM-B stands for (C)apability, (O)pportunity, (M)otivation, which are three pre-requisites for (B)ehavior. It was developed by Susan Michie, Maartje van Stralen, and Robert West in 2011. It is also connected to the behavior change wheel which goes into more depth than the initial acronym, breaking Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation into two sub-categories each.

Strengths

COM-B strikes a great balance between simplicity and complexity. It’s (relatively) easy to explain to stakeholders without sacrificing depth, thanks to the sub-categories and the broader Behavior Change Wheel. This makes it a solid choice for organizing behavior change projects.

Weaknesses

COM-B doesn’t always align with how people naturally think. For example, in projects involving social norms or habit formation, the issues and solutions can span all three components—Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation—leaving me uncertain about how to represent it all without causing confusion. Additionally, splitting motivation into “automatic” and “reflective” is slightly strange to me, forcing motivation into a dual process despite such dual process theories not being about motivation. Lastly, COM-B was developed in a public health context, and it perhaps performs best in that domain.

Final ranking

In my opinion, COM-B is one of the best frameworks available. It’s not perfect for every project, such as when you are working with concepts that bridge the categories too much, or when you want more specificity. Nevertheless, it works for many and balances complexity and simplicity well. Though I might have a bias here—much of my work has been in the health domain where COM-B really shines.

Still, S-Tier without any hesitation.

Fogg Behavior Model

The Fogg Behavior Model (FBM) is the framework I have gone back and forth the most on for this series, and I've been on both sides of the aisle; anti- and pro-FBM. The ranking you'll find here is actually a re-write because I no longer endorse my original post. This post will also be longer because I am writing it after having finished the series on LinkedIn and so no longer have a character limit. I am also going to be more liberal about using images since a big part of this framework is the visual component. (Note on terminology: FBM is both a model and a framework, and I will call it both at times)

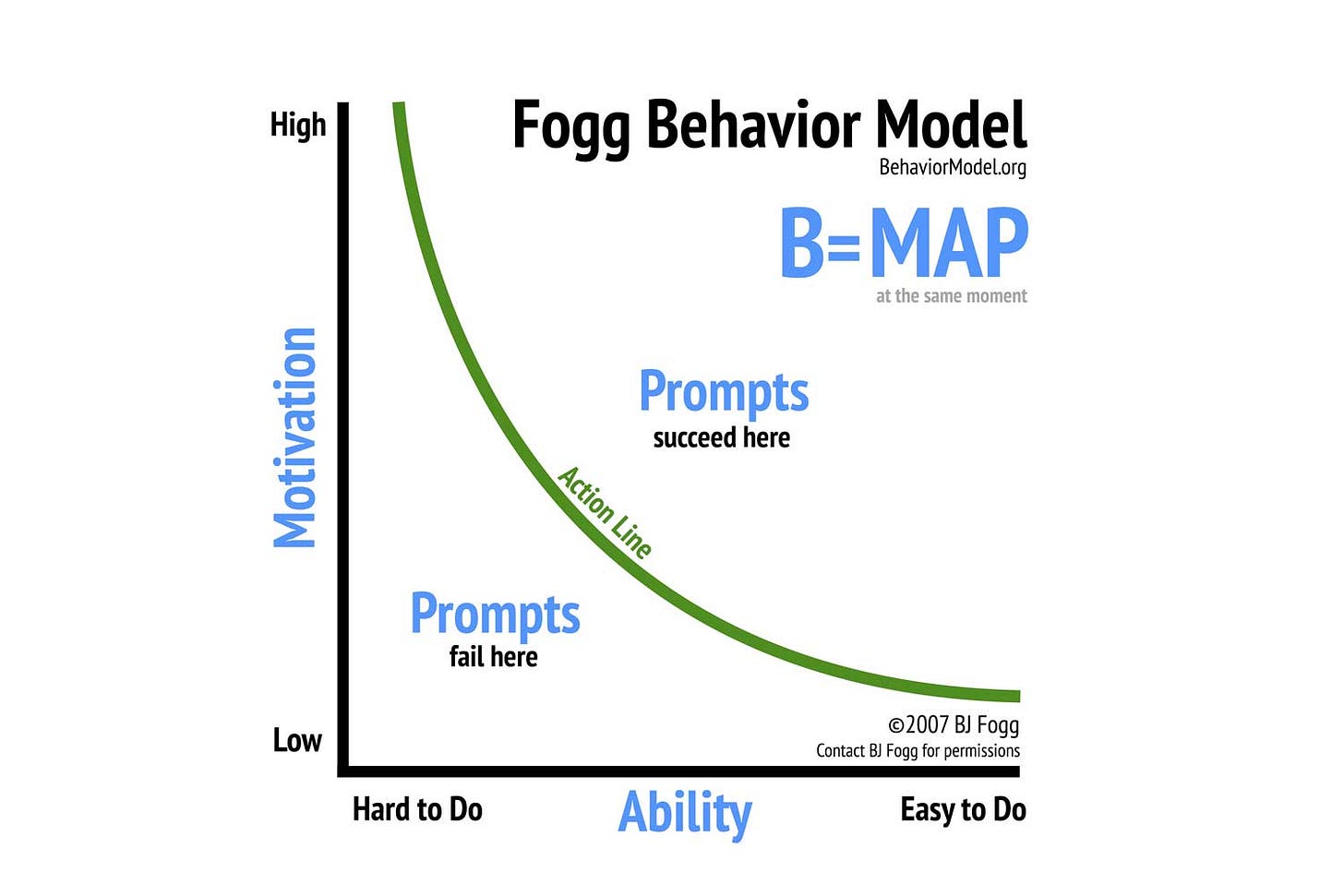

What is FBM

FBM was developed by BJ Fogg and bridges the line between framework and model. The framework says that (B)ehavior happens when there is sufficient (M)otivation and (A)bility and there is a (P)rompt, giving us the equation B=MAP. It likely has the distinction of being the most used behavior change framework by non-behavioral scientists, informing the development of some of the world’s biggest apps.

Overall, the acronym BMAP is very similar to COM-B, another behavioral framework, which also has Motivation, but splits Ability into Capability and Opportunity, and doesn't have the prompt in its acronym. Though it was created four years earlier (2007).

But then Fogg does something interesting and represents these factors on a chart. This is the model. The model is intuitive and is pretty effective for explaining things to clients. This intuitive representation is a big reason why it's so big in Silicon Valley.

Strengths

I recently spoke with BJ Fogg about his model, and he showed me some additional things he does with it I hadn't seen before.

The first is that he actually splits ability and motivation into opposing forces of motivators, de-motivators, facilitators, and frictions. So for example, if you want people to drink more water, you can think about increasing motivators, decreasing de-motivators, increasing facilitators, and decreasing friction.

The next is that he puts the alternative behavior on the same chart, and so not only does the chart get you to focus on a single behavior, but also gets you to think about how to decrease the alternative behavior. The idea is that which ever behavior is furthest from the prompt line is the behavior that will be done. So in this example, even though both behaviors cross the line, drinking soda is further beyond it, making it the more likely behavior. Rather than focusing on increasing motivation to drink water, maybe you should think about how to increase friction to drink soda.

Another nice thing is the way it handles a distribution of people. Just a nice representation for thinking through population behavior change, and for thinking about segmentation as well.

Weaknesses

Dr. Fogg is a controversial figure in this field. I've been warned of reputational risks if I defend it. Elina Halonen has written two articles (1, 2) critiquing the model and its academic credentials. I originally endorsed one of those articles.

I no longer endorse those criticisms. Elina is a careful thinker who I respect a lot, which is why I took her criticisms at face value. But I do think she got this one wrong. At some point I should probably write up a response to Elina, but I'm just not sure what appetite she or I have for the emotional, social and temporal costs of a debate. For now I'm happy to just say I disagree with her criticisms and tell everyone my mind has been changed.

However, I think it is worth mentioning why this model is so controversial.

Dr. Fogg is not a traditional academic. Rather he is a business owner, and so does things differently than academics like. He isn’t concerned about publishing academic papers and so you have to go through his books, lectures, and website to learn about the model.

(EDIT: Dr. Fogg responded to this and said that although academic publishing is not a top priority at this stage of his career, his publications have had significant impact. He recommends checking out the citation stats at his Google Scholar page (TLDR: over 29,000 citations). I apologize for the error.)

(EDIT 2: It is also worth pointing out that Dr. Fogg spent 30 years at Stanford where he conducted research and taught graduate seminars. I do think he is not a typical academic, and Dr. Fogg says as much. But I shouldn’t over emphasize the differences either.)

These non-academic sources are often lacking careful citations, and so it’s not always clear what is original to him, and what may have been inspired by the work of others. Additionally, his model is personally copyrighted, which goes against the norm. All of this together rubs many Behavioral Scientists the wrong way, and even strikes some as unethical. Dr. Fogg is also closely attached to Silicon Valley and many blame him for some of the addictive elements that tech companies add to their products.

However, none of this really affects the efficacy of the model, and mostly strikes me as completely normal for anyone outside of academia. The last point about his model being using to make apps addicting strikes me as pretty unfair. Additionally, the copyright doesn’t prevent anyone from using it, and is only there to prevent people from changing the model and then attributing the changes to Fogg (which I have seen people do even with the copyright). Matt Wallaert mentioned on my original post that we were just “debating personalities” when we were debating this model, and I think there is an element of truth to that.

I’ll leave it to others to gauge how important this stuff is to them, but it doesn’t ultimately effect the efficacy of his framework.

I am still confused by his model of motivation, and I want to better understand how his framework connects back to habits, as the model itself doesn’t seem to capture that aspect. But for the most part, the critiques thrown at the model have increasingly struck me as unfair as I have dug further into the framework.

Final Ranking

My opinion has been all over the place with this framework. But ultimately, there is a good reason this model is so popular in Silicon Valley; it is intuitive, and great for helping clients think through the basics of behavior change.

S-Tier.

(Original post which I no longer endorse)

Ten Conditions for Change

Five posts into the #FrameworkTierList series, and now it’s time to talk about a lesser-known (and hopefully less controversial 😅 ) framework: Ten Conditions for Change.

What is Ten Conditions for Change (10CC)?

While no one (as far as I know) uses this acronym, 10CC was developed by Spark Wave, a start-up foundry run by Spencer Greenberg. Spark Wave has a number of cool products, like the Clearer Thinking website and podcast, that might interest behavioral scientists (I recommend the interview with Daniel Kahneman). 10CC combines 17 different frameworks into one model, with an accompanying free survey that helps users try to change a behavior in their own lives. The framework consists of three phases and 10 conditions, all presented on a very user-friendly website with great references throughout.

Strengths

10CC is a fantastic reference. I’ve used it on several projects, and it’s become one of my go-to resources to ensure I’m not missing anything—whether it’s a phase, strategy, tactic, or potential failure mode. Although it combines 17 frameworks, the website's format makes it easy to navigate and find what you’re looking for. In fact, I even used it to help decide which frameworks to cover in this series!

Weaknesses

The main downside is that behavior change is rarely as linear as 10CC suggests. Behavior happens in complex contexts, and trying to force it into 10 neatly defined conditions can feel a bit overwhelming, which is why I use 10CC more as a reference—picking out what’s useful for the project at hand rather than following it as a step-by-step process which the audience I am working with must go through.

Final Ranking

I like 10CC—it’s aesthetically pleasing and easy to use. I highly recommend checking it out (as well as other Spark Wave products). But the goal of this series is to rank frameworks based on how well they can organize an entire project, and that’s not really what I use 10CC for. Instead, it’s better as a reference tool to help make your change strategy more comprehensive.

Final Verdict: B-Tier (but ahead of Behavioral Drivers Model due to its ease of use).

Opposing Forces

Six posts in, and I think we may be hitting the halfway point of the #FrameworkTierList series. I don’t want to do this forever! Sure, there are things that push me to continue. The engagement fuels me, and the intellectual challenge drives me along. But there are also things that pull me away. Barriers and friction in my path. My approach and avoidance instincts pull me in opposite directions here at the midpoint of the series. With all of these opposing forces perhaps it is time to talk about exactly that.

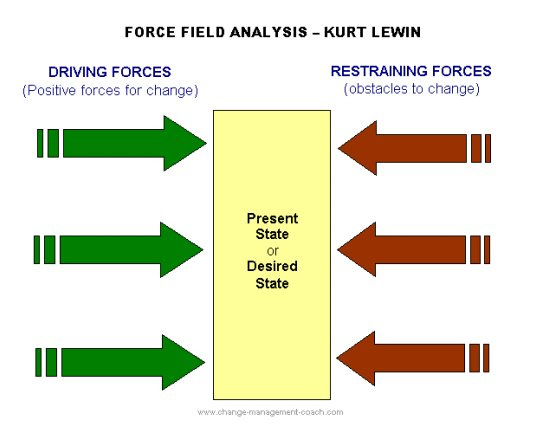

What is Opposing Forces

“Opposing Forces” is one of the simplest ways to think about behavior, which is why it appears everywhere—barriers and drivers, 3Bs (Behavior, Barriers, Benefits), push and pull, approach and avoidance, or Friction and Fuel. Kurt Lewin’s Helping and Hindering Forces in his “Force Field Analysis” framework is in many ways the origin of all these later frameworks.

Matt Wallaert describes the basic idea very well on his website: “All decisions and behaviors are the product of two opposing sets of forces—reasons to do something (promoting pressures) and reasons not to (inhibiting pressures).”

Strengths

Can you even do Behavioral Science without considering opposing forces? It’s so fundamental that I questioned including it in this series. But Matt Wallaert has championed it in the comments, and I get it—thinking about opposing forces is essential. It is perhaps always there implicitly even when using another framework. And some of them, like Friction and Fuel, have sub-categories and solid a metaphor to latch onto that help make them a little more concrete, which I really like.

Weaknesses

But what about all the other stuff! I want a framework that will help me figure things out, and to remember what I might otherwise forget. I have a hard time believing that the solutions generated by thinking about “barriers and drivers” can match the quality and diversity of those produced by other frameworks.

Final Ranking

Tier lists are terrible. Whose idea was this anyways!? And why did I decide to rate these frameworks together? That's just stupid.

Of COURSE Opposing forces deserve S-Tier. It is fundamental, and implicitly I am always framing problems as barriers and drivers anyways.

But also…come on! I want to give it low tier just for being lazy.

I am conflicted. Pushed and pulled. Caught in the middle of opposing forces.

Fine. To A-tier it goes.

(Original post) - Note that in my original post I used the Friction and Fuel image. I came to regret that, since I wasn’t evaluating that framework specifically, but the general idea of opposing forces. Friction and Fuel itself probably would deserve a higher tier than Opposing Forces, as it gets into more specifics.

Self-Determination Theory

Post number 7 in the #FrameworkTierList series, and this might be the one that gets me canceled—today I’m talking about why I think Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is wrong.

What is SDT?

SDT, developed by Richard Ryan and Edward Deci, is incredibly influential. They proposed that there are two types of motivation—Intrinsic and Extrinsic—and that three factors (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) drive the former. Based on their studies, they then argued that increasing Extrinsic Motivation (such as by paying subjects) undermines Intrinsic Motivation.

SDT is unique in this series because it is first and foremost a theory, but is often used as a framework. I think it is important to talk about both aspects.

SDT as a theory

Steven Reiss criticizes SDT in his book "Myths of Intrinsic Motivation." At 68 pages it is worth the read. Here's a major conclusion from the book. Note, it is a rather bold claim.

“Extrinsic motivation does not exist; all motivation is derived from intrinsically valued goals common to everyone and deeply rooted in human nature. Both psychometric science and neuropsychology strongly suggest that human needs are not divided into two types. This implies that the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is invalid.”

In addition to denying the distinction between the two types of motivation, he also argues persuasively against the undermining effect, something Behavioral Scientists have also been critical of.

Reiss has convinced me. In my opinion, there is nothing unique about autonomy, competence, and relatedness, and extrinsic motivation doesn’t exist. Additionally, the undermining effect is more nuanced than the SDT theorists claim. I believe SDT is likely wrong in most, if not all, of its major claims.

This opinion makes me a minority in my field, and I'm sure I'll get called out in the comments. It's also unlikely a LI post will convince anyone, but I hope I've made people a little more curious about the criticisms.

SDT as a framework

Without the theory to back it, SDT is mediocre at best. No framework is comprehensive, but SDT is particularly narrow and shouldn't be used on its own. Even concepts that feel like they should be included are missing, such as meaning, enjoyment, curiosity, etc.

(It might be an OK framework for thinking about workplace culture. But even there it's pretty narrow and too abstract.)

Final Ranking

I would put SDT in the lowest tier, but it's got decades of research around it. For that reason, I can't judge others too harshly for using something so well-vetted. Epistemic humility and my own self-doubt prevents me from relegating it too low.

Still, I can't force myself to put a theory I believe to be wrong higher than the bottom of B-Tier.

For a good overview, read this Substack by Frazer Mawson.

Elephant-Rider-Path

In Hindu cosmology, the world rests on the backs of eight elephants. So, for post number 8 in the #FrameworkTierList, it’s time to talk about elephants.

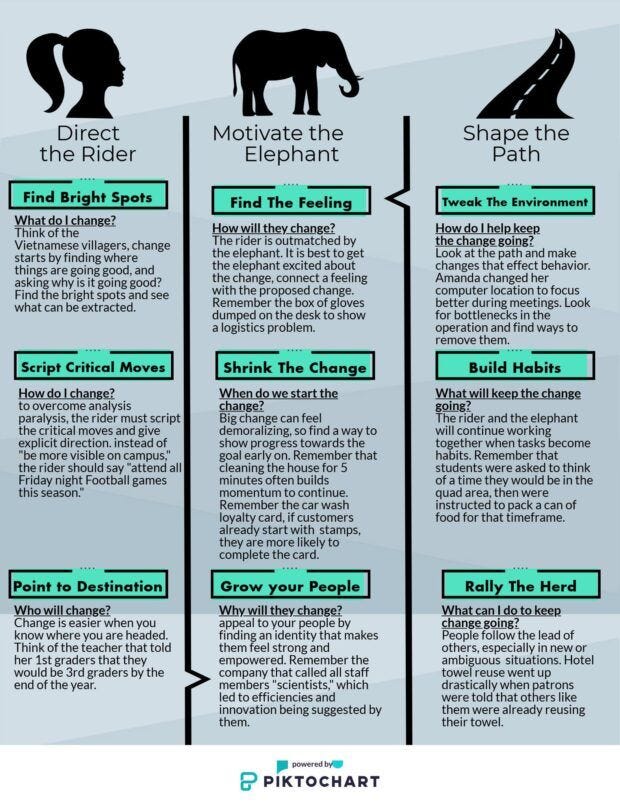

What is Elephant-Rider-Path (ERP)

Developed by Chip and Dan Heath in their book Switch, ERP is a framework based on the metaphor of a rider and an elephant. The metaphor represents the tension between what we think we should do (rider) and what we’re actually motivated to do (elephant). To change behavior you need to direct the rider, motivate the elephant, and shape the path. You can see more specific advice about what that means in the attached chart.

Strengths

I know it’s a bit silly, but sometimes silly works for the right audience, and I actually like this.

The metaphor of the elephant and rider is old, with the Heath bros getting it from Jonathan Haidt’s The Happiness Hypothesis, who himself got it from ancient Buddhist teachings. A similar metaphor with a horse and a charioteer was used by Plato. It’s a good metaphor for thinking about why behavior change is hard!

The framework itself is also pretty nice and I think many would benefit from better understanding the 9 pieces of advice. I especially appreciate the focus on ‘bright spots’.

Weaknesses

It’s not really a framework that Behavioral Scientists use. Perhaps it’s too simple, too simplistic, or the categories and advice not MECE (Mutually Exclusive or Comprehensively Exhaustive).

But I suspect one of the main reasons we don’t use it is aesthetic. Imagine going to your Super Serious Corporate Client and saying the framework you use involves elephants. It doesn’t *seem* scientific, and it is easy to imagine losing credibility because of that perception.

(Is there a term for this in the literature? The Halo/Horns Effect would be appropriate, but I wonder if there is a better term for it.)

Final Ranking

For non-behavioral scientists, ERP is a solid starting point. It helps make behavior change more tangible and helps align stakeholders with a good metaphor. For that reason it is an effective framework for organizing projects.

Sure, it’s not perfect, but it is actually a pretty good starting place: A-Tier.

Psych

So far, I’ve avoided putting any framework in the lowest tier of this #FrameworkTierList series. After all, why discuss a framework about which I don't have much nice to say? But for the sake of completeness, I’ve decided to review one that (spoiler alert) I’ll put in the actively avoid tier: The Psych Framework (Psych).

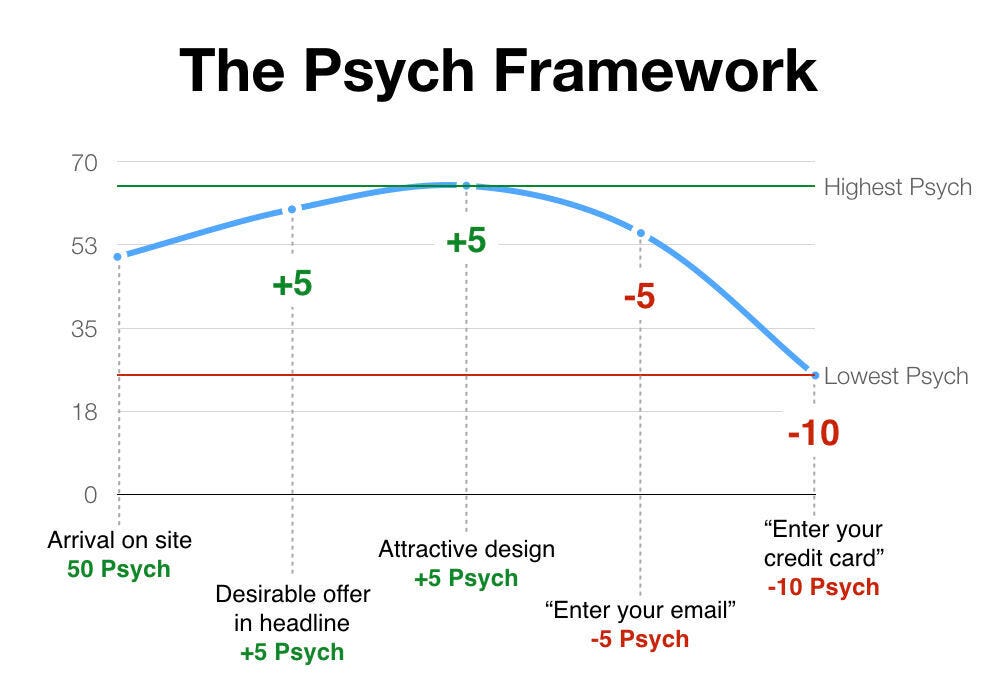

What is Psych?

Psych aims to simplify behavior change for product teams by introducing “psych levels”—an intuitive measure of user motivation. The idea is that by increasing a user’s psych level during a digital engagement, teams can nudge them toward desired actions.

Strengths

For straightforward digital engagements, Psych’s simplicity is appealing. It’s easy to understand, providing product teams with a starting point for considering what might influence user motivation during specific points in the user journey. Psych is especially helpful for teams without a behavioral science background, as it’s accessible without much technical depth. The website Growth Design is a great example of Psych in action, using the framework to highlight what works and what doesn’t in UX.

Weaknesses

The biggest issue is that “psych level” isn't scientific and reflects a rather naïve view of behavior change. Motivation isn’t a bouncy ball that rises with every good feature and falls with every bad one. Real motivation is multi-layered, shaped by internal beliefs, social dynamics, and context.

So, if Psych isn’t measuring true behavior change potential, what is it actually measuring? “Measure” might be generous, as psych levels are often estimated on the fly. But to the extent that it captures something real, it’s trying to capture something like short-term engagement potential—essentially, the immediate allure of an experience rather than the deep-seated motivation needed to maintain behavior.

You can think of it in terms of the concept of "little e" behavior change, as described by Cole-Lewis, Ezeanochie, and Turgiss (2019). Little e behavior change refers to engagement with the intervention itself (e.g., interacting with an app), while "Big E" behavior change focuses on the target behavior the intervention aims to produce (e.g., an exercise habit).

Final Ranking

Psych’s emphasis on little e engagement has value and can deliver small wins for digital engagement. But its oversimplified view of motivation and lack of construct validity means I can't quite endorse it, and that I would never use it for a behavior change project.

Final Verdict: D-Tier

Opportunity Solution Tree

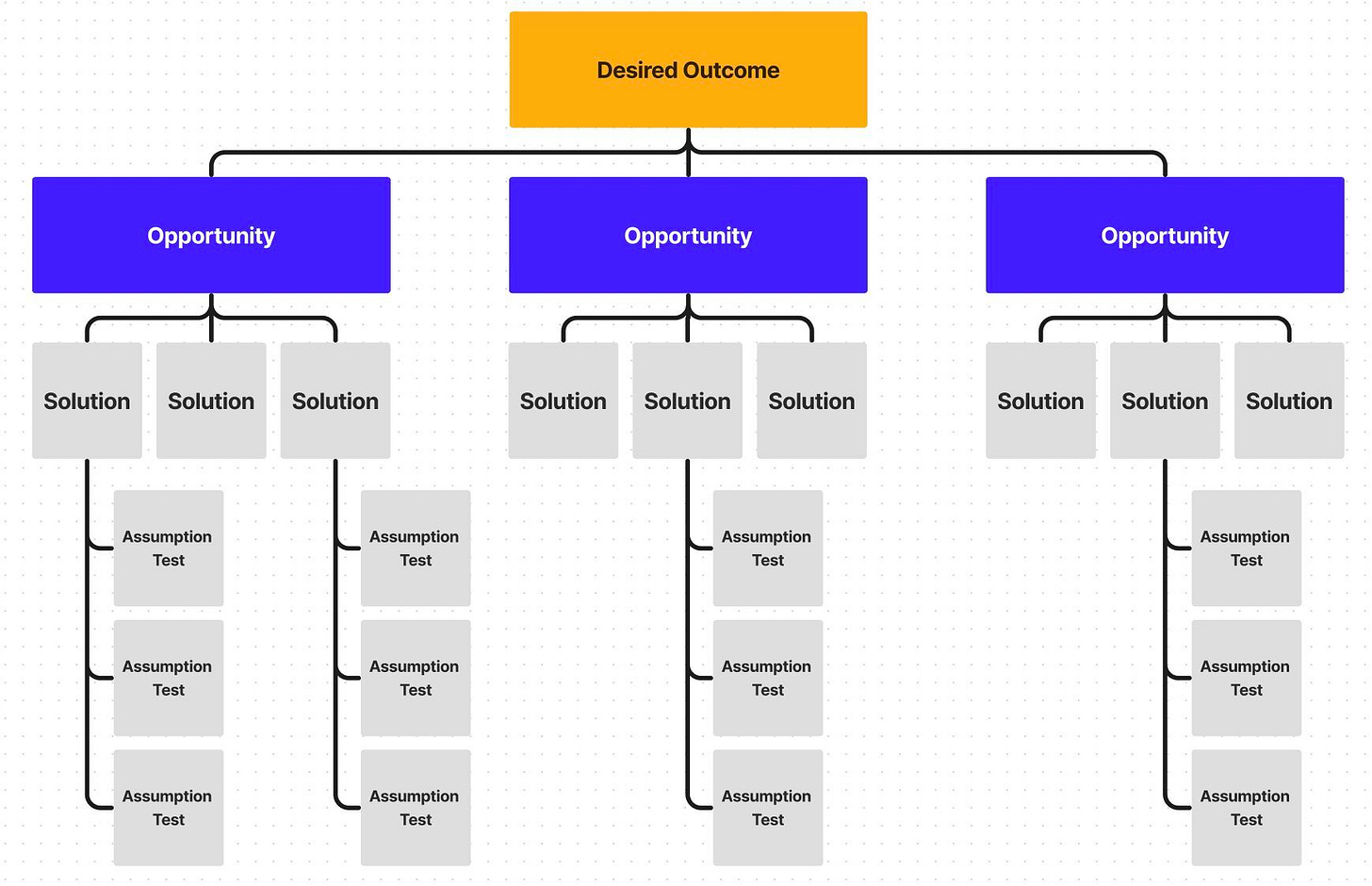

This #FrameworkTierList entry is a bit different, as the Opportunity Solution Tree (OST) isn’t a framework itself but an approach for creating them. It is also not specific to Behavioral Science, but I recently discovered OST and realized it mirrors what I do when developing custom frameworks for clients, so I’ll treat it like one.

What is the OST?

The OST helps organize and connect a key behavior to the opportunities and solutions that encourage it. It starts by identifying a key behavior (e.g., recycling plastic containers) and then uncovering the beliefs, thoughts, feelings, or behaviors that inhibit it (e.g., worrying about cleaning it sufficiently). Once the problems are identified and thoroughly understood, a rich and detailed understanding of 3-4 core opportunities is created.

For me, the creation of these “opportunities” is where the magic of behavioral science happens. Once the opportunities are clarified in sufficient psychological detail, something often clicks for teams, and it becomes clear what must happen. The problem is no longer abstract, vague, or confusing. Instead, there are concrete opportunities fleshed out in detail, making it clear to everyone what the problem is and how it must be addressed. Often, it’s during this stage that clients realize how behavioral science can turn messy problems into something intelligible and actionable. I have written about this twice, here and here. The result of a well-developed OST is that everyone understands what needs to happen, becomes aligned, and creative powers are unleashed. At that point, it doesn’t require behavioral scientists to create "nudges," because the whole team is involved in making sure the opportunities are carried out.

Strengths

The Opportunity Solution Tree is an incredibly effective approach. It aligns teams, clarifies the path forward, and is easy to understand and communicate. It’s also highly adaptable and personalized, making it great for tailoring a general framework into something specific for the client.

Weaknesses

It’s not a framework in itself but rather an approach for framing a project. For more structure, you might need to integrate a secondary framework. Also, it’s not specific to Behavioral Science, so additional support may be needed to fully integrate Behavioral Science into the approach.

Final Verdict

In my view, every behavioral scientist should be using something like this approach. It clarifies problems for teams, and keeps behavior change projects organized. While it doesn't suggest solutions, it nevertheless provides a good structure into which you can integrate solutions.

Final verdict: S-Tier. And I will even put it ahead of COM-B.

Make It

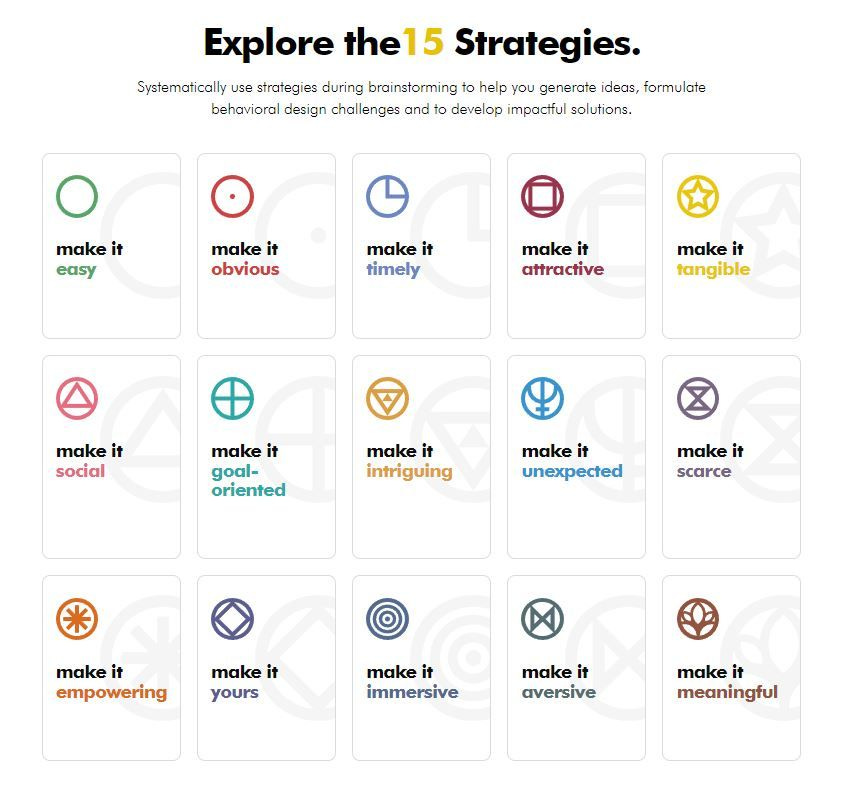

Last framework in the #FrameworkTierList series! Time to review the Make It Toolkit.

What is the Make It Toolkit?

Created by Massimo Ingegno, The Toolkit consists of 15 strategies to consider when trying to change behavior, from “make it attractive” to “make it yours.” It offers an intermediate level of detail between abstract concepts like “motivation” and specific interventions like “social norms.”

Strengths

This level of description resonates with me quite a bit. Some frameworks dive into interventions too quickly, while others are too abstract, saying vague things like “increase motivation” or “persuade” without making it concrete how to do that. The Toolkit provides a consistent, intermediate level of analysis that’s easy to translate across frameworks and also between Behavioral Scientists and non-Behavioral Scientists.

It’s particularly effective for organizing projects. Each strategy, while broad, can be tailored to the specific project (e.g., making it meaningful…by providing immediate feedback that connects behavior to purpose). And while 15 strategies are too many for any one project, The Toolkit pairs well with the Opportunity Solution Tree (reviewed last week) to help prioritize strategies and link them to interventions.

Weaknesses

The Toolkit doesn’t feel fully comprehensive, so I often add my own categories like “make it rewarding.” I also tend to split 'make it social' into more specific categories (e.g., make it a social experience, make it normalized, competitive, authoritative, or accountable). 'Social' feels too vague. That said, too many strategies can become overwhelming and so I understand why the cut-off is 15 strategies.

I’m also not always compelled by the specific Behavioral Science interventions suggested under each strategy. I treat them as reminders of potential tools that might-maybe-could-potentially-possibly work rather than concrete recommendations.

Final Ranking

This is my favorite Behavioral Science framework. It strikes the right balance of detail, making it easy to coordinate with clients and integrate with other frameworks. While not comprehensive, it’s easy to add your own category as needed. And while it offers too many strategies for any single project, prioritizing and pairing it with the Opportunity Solution Tree resolves this issue. What’s not to like?

Final verdict: S-Tier. Not just in the top tier, but the best framework in the top.

And for now, that is all the frameworks I am going to evaluate. There are others, of course; The Health Belief Model, The Transtheoretical Model, various Opposing Forces models, OCTALYSIS, Misperceptions and Inactions (which I helped create), The Theory of Planned Behavior, MINDSPACE, and BASIC. Not to mention the various habit, personality, ethical, and process frameworks. But I had to cut myself off somewhere.

It is also important to remember what I have done here. I was criticized by a couple of people for doing this tier list, and I am sympathetic to the criticism. The purpose here was to generate discussion, not provide the One True Ranking. So I’ll end this post with a reminder of what this tier list actually represents: usability for organizing a behavior change project, which is not what all frameworks are trying to do. And in some cases, it is completely unfair for me to rank frameworks on this criterion for that reason.

I’ve said it before, and I will continue to say it: every scientifically informed Behavioral Science framework is S-Tier for some context. Sometimes frameworks work exceptionally well for one project, even if they’re challenging to apply to another. Probably what I should have done is clarified each framework’s S-Tier context, but part of what I hoped to accomplish in doing this series is to clarify WHY some models just work better for one project or another because it is not always even clear to me. I don’t have a full answer to that question yet, but I look forward to doing a write-up of what I did learn in the coming weeks. (Update: That article can be found here)

Fantastic post, Jared!

This is extremely valuable. There are too many compendiums of behavioral biases and not enough collections of frameworks. More important than the rankings is the critical thought you have put into the discussion of strengths and weaknesses. Thank you!