In the psychology of decision-making, there are, shall we say, disagreements.

Some of these disagreements are minor—academic quibbles that no one outside a conference panel would care about. Others are so fundamental that they’ve splintered the field into isolated research communities that rarely engage, except, perhaps, to critique one another.

These factions are often called by various names; schools of thoughts, research programs, and paradigms. And while some of their differences get exaggerated for dramatic effect, the underlying divides are real and substantial. It's difficult to capture the intricate relationships between these schools of thought over decades of research and among thousands of researchers in a short article. But to say there has been contention is no exaggeration.

In my mind, there are four major schools of thought1, each of which go by a two- or three-letter acronym. Some of these schools developed in tandem, and others in reaction to each other, in what has sometimes been dubbed "The Great Rationality Debate"2. The differences between these are not merely scientific but often stem from basic assumptions about the nature of humans and reality.

I thought it might be fun to provide a little more context on these schools so that I have something to point to when I talk about them later. This will be more primer, and less in depth analysis. Though I will include lots of resources at the end for those who want to dive in more.

School 1: Classical Decision-Making (CDM)

CDM isn’t the first approach to decision-making ever developed, but it’s where our story begins—because every other major school of thought emerged, and continues to evolve, in response to it.

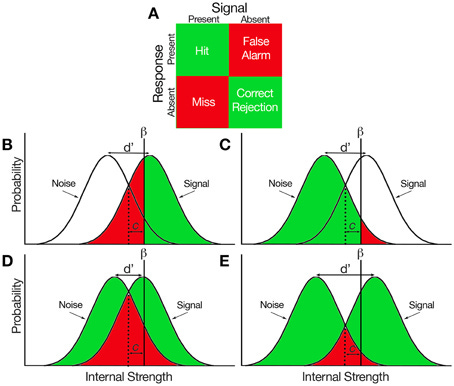

At its core, CDM assumes that rational decisions can be determined mathematically and logically. Unfortunately, that means we have to start with the driest of the schools. CDM is built on mathematical and economic models, including Decision Theory, Game Theory, Opportunity Cost, Bayes’ Theorem, and Signal Detection Theory.

CDM is cold, precise, and unyieldingly mathematical—which might explain why economists love it.

Or is that unfair? Maybe economists have a reputation for being cold and mathematical because their discipline was built on CDM’s foundation. Either way, their attachment to it comes down to two key reasons.

First, within an economic model, CDM produces the optimal results. In other words, if you accept the premises of the model, then applying CDM isn’t just useful—it’s rational by definition.

Second, CDM is surprisingly descriptive. While the average consumer isn’t explicitly running Bayesian updates in their head, their behavior often resembles CDM predictions. People frequently act as if they’re following these principles, even if they’ve never heard of them.

This dual role—both prescriptive (what people should do) and descriptive (what people actually do)—makes CDM a compelling framework. Of course, even its proponents vary in how strongly they endorse each claim. But as the saying goes, all models are wrong, yet some are useful—and CDM seems to be useful on two fronts.

My Take

I like CDM. More people should learn to think like an economist and apply its tools. That said, I’m cautious about using it indiscriminately. A common mistake—made by both critics and advocates—is equating CDM with rationality itself. In reality, CDM is often suboptimal in the real world for the simple reason that the real world isn’t a tidy economic model. And despite claims of the accuracy of CDM models, they really aren’t as predictive as economists sometimes claim.

School 2: Heuristics and Biases (HB)

In the 1970s, two Israeli psychologists, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, began to question the assumption that people were rational in the way proponents of CDM claimed. They weren’t the first to do so—Herbert Simon, Friedrich Hayek also had questioned it, and OG economists like Adam Smith would have balked at the very idea that people were so rational. And to be fair, most economists saw CDM as a useful model rather than a literal description of human behavior.

But Kahneman and Tversky provided a methodology to understand how people diverged from CDM, in what they called the “psychology of single questions.” And with this method, they showed that people deviated systematically from CDM. This was extremely disruptive for economics, and incredibly important for psychology.

Here is an example of some of these single questions. Try doing these three questions as quickly as you can

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

If it takes 5 machines 5 minutes to make 5 widgets, how long would it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets?

In a lake, a patch of lily pads doubles in size every day. If it takes 48 days for the patch to cover the entire lake, how long would it take to cover half the lake?

Check the footnotes for the correct answer.3

What’s interesting isn’t just that most people get these wrong—it’s that they get them wrong in the same way. The consistency of these errors suggests that people rely on similar mental shortcuts when reasoning. This is important for three reasons.

First, Kahneman and Tversky were working in the wake of Behaviorism, which had tabooed the study of thought processes. Their “psychology of single questions” provided a very simple methodology for studying the systematic thought processes that underlie behavior (i.e., the mind). This was a major development in the field of Cognitive Science.

Second, since the errors were systematic, economists could, in theory, adjust their models to account for them—modeling behavior as CDM + bias. And again, in theory, this could lead to more accurate and predictive models.

(Politically this was important too. Economics is more prestigious, and gets taken seriously by politicians. By being able to point out how ridiculous economic models were, psychology gained some much desired prestige.)

Third, if biases were systematic, maybe they were also fixable. This inspired efforts to de-bias, nudge, and budge people toward better decisions—helping them think more like CDM prescribes.

Any one of these contributions would have been a major breakthrough. Together, they propelled Kahneman and Tversky to academic rock star status, ultimately earning Kahneman a Nobel Prize in 2002 (Tversky had passed away by then). Their work was further popularized by Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow in 2011, a surprisingly successful book given how dense it is.

The research paradigm that emerged from this work is called Heuristics and Biases (HB)4. The heuristics are cognitive shortcuts people use to simplify decision-making, and the biases are the systematic errors these shortcuts can lead to5.

For example, rather than calculating Expected Utility in a moral dilemma like the Trolley Problem, people might rely on a Do-No-Harm heuristic, which simplifies the decision but introduces a systematic deviation from what Expected Utility would predict. This systematic deviation we call “Omission Bias.”

It’s important to clarify: biases are not deviations from rationality itself, but from CDM. Many people miss this distinction when first encountering HB. Many think that anything with the name “bias” must be irrational and bad. But consider the fact that many people endorse the Do-No-Harm Heuristic as a categorical imperative to follow, and you will start to understand how “biases” aren’t always errors. A table makes this a little more clear6:

My Take

I was trained in the HB tradition, and I have a soft spot for it. But I also think it has serious limitations.

As a scientific paradigm, I suspect HB has outlived its usefulness. Simply collecting lists of biases isn’t all that interesting or helpful, and it can be actively misleading when used to declare humans irrational just because they deviate from CDM. Some decisions that rely on heuristics or produce biases actually make sense in context. We need to stop focusing on biases, and get a better understanding of the cognition. After all, “rationality” is not a solved problem, and therefore finding deviations from "rationality” is not useful in most situations.

And despite all the psychological taunting, economists still largely ignore biases in their models—not out of stubbornness, but because heuristics aren’t as systematic as once thought. Replicability and generalizability have turned out to be major issues. In other words, the HB revolution may have been built on shakier ground than we realized.

School 3: Fast and Frugal (FF)

I always imagine Gerd Gigerenzer as the kind of guy who will be your best friend until you anger him even once.

That’s certainly an unfair caricature, but it’s hard to escape the indoctrination of the HB researchers that trained me. And to be honest, Gigerenzer does sometimes come across as a little angry and, at times, unfair to HB.

Gigerenzer is the founder of Fast and Frugal (FF) decision-making, also known as Ecological Rationality. FF emerged as a direct challenge to Kahneman, Tversky, and the wider HB research program they founded.

Gigerenzer’s main issue with Kahneman and Tversky is that they don’t go far enough in rejecting the mathematical models of Classical Decision-Making. Kahneman and Tversky treat those models (e.g., Expected Utility, Signal Detection, Bayes Theorem, etc.) as an unrealistic description of human behavior—yet they still cling to it as the correct standard for rationality. Gigerenzer won’t have that. He argues that these mathematical models aren’t just an inaccurate model of how people make decisions—they are also bad models of how decisions should be made.

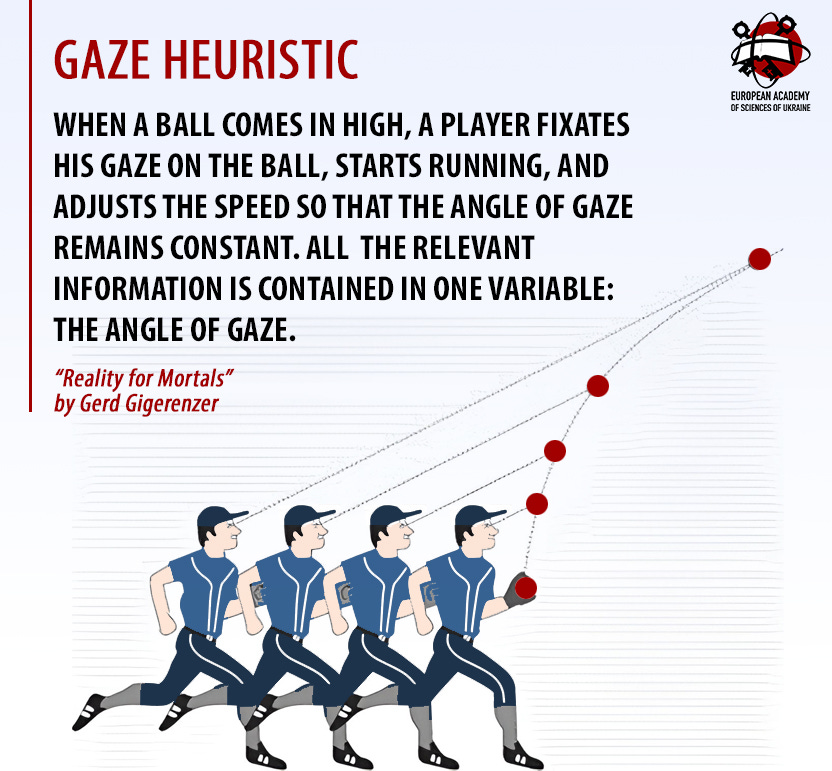

Where Kahneman and Tversky view heuristics as leading to systematic errors, Gigerenzer sees them as fast and frugal—quick, efficient rules that take advantage of environmental structure. In his view, heuristics aren’t just cognitive shortcuts; they are ecologically rational, meaning they work because they exploit real-world information in an efficient way.

One of the classic examples Gigerenzer provides is that of catching a ball. In theory, you could predict its landing spot using complex calculus and physics equations. But in practice, people use the Gaze Heuristic—keeping the ball in the same spot in their visual field while moving. This simple rule ensures that the ball will land right where you're looking. If you’re smart, you’ll raise your hands and catch it before it smacks you in the face.

Or consider investing. In 1990, a Nobel Prize was awarded for Modern Portfolio Theory, a mathematically complex strategy for optimizing investments. But once you dig into the math, you realize the theory is only optimal over timeframes longer than a human lifespan. If you instead apply the 1/n heuristic—simply dividing your money evenly across n investment options—you’ll perform just as well as the Nobel prize winning research, but with much less effort.

The takeaway? Seemingly dumb heuristics can outperform mathematical models. So why are Kahneman and Tversky calling people irrational for using heuristics and insisting they should rely on complex, computationally expensive models instead? What is rational about that?

Gigerenzer fired the first public shots by publishing a scathing critique of HB. Kahneman and Tversky responded, accusing him of misrepresenting their work—they didn’t see themselves as arguing that people were irrational7, but as falsifying Rational Choice Theory, a main theory of Classical Decision-Making. But regardless of their intention, that’s certainly how many researchers interpreted the work. This exchange kicked off the modern Great Rationality Debate, centered on this question: "Are people rational?"

The debates were intense. The debates ARE intense. To this day, the HB and FF camps rarely interact—except, perhaps, to complain about each other. HB researchers (mostly in the US and Israel) focus on how heuristics lead to biases, while FF researchers (mostly in Europe) focus on demonstrating how heuristics are rational and adaptive. In my opinion, the divide represents a pretty hideous and unnecessary scar in the field of decision-making. For the love of all that is holy, please kiss and make up already.

My Take

FF is fine for what it is—a necessary pushback against the overinterpretation of heuristics as irrational, and deep exploration of those heuristics. In some ways I prefer their approach to the collect-a-bias paradigm that HB has become. HB researchers should pay more attention to their FF colleagues. Most heuristics are rational and adaptive in real-world contexts, and it’s important to understand why.

That said, FF researchers sometimes go overboard in defending heuristics and don’t seem to have a well-developed theory of errors. Heuristics can fail, and a robust theory of decision-making should account for both their strengths and their limitations. I also find FF to sometimes be a little too narrow in scope—this is a disposition I share with our next school of thought.

School 4: Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM)

While the HB and FF camps were busy clashing within the halls of academia, Gary Klein was pioneering something revolutionary out in the real world. Enter Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM).

NDM’s origin story begins with Klein’s interviews of firefighters. The project got off to a rocky start when, in the very first interview, a fire chief told Klein it would be a short conversation because he had never made a decision in his entire career.

Puzzled, Klein asked what he meant. The chief explained that he simply followed procedures. Dismayed, Klein asked to see the procedures. The chief clarified, “Well, they’re not written down.”

Turns out the chief did make decisions, just not in the way many people assume. What the fire chief meant was that he didn’t make decisions in the way CDM describes—by generating, evaluating, and comparing options. Instead, he (like most experts, from healthcare providers to pilots to chess masters) typically recognized the right course of action immediately. He didn’t compare multiple options—he just knew.

To explain this kind of decision-making, NDM introduced concepts like pattern matching, Recognition-Primed Decision Making (RPD), and Data-Frame Theory of Sensemaking. This was something entirely new—neither the simplistic heuristics studied by Gigerenzer nor the biased ones highlighted by HB researchers.

NDM researchers were able to discover all of this because they used a completely different methodology than the other schools of thought. Unlike most psychologists which relied on lab experiments with undergrads, NDM studied professionals in high-stakes, complex environments. As it turns out, decision-making in the real world looks very different from decision-making in a psychology lab. In the real world, breaking down what people do into single heuristics loses too much nuance.

NDM thrives on stories, so here’s a classic one:

Klein once interviewed a firefighter who swore he had ESP (extrasensory perception). Naturally, Klein was skeptical, but he asked him to explain.

The firefighter explained a strange incident he was in where he and his crew were fighting what seemed like an ordinary fire—but then he got a bad feeling about it. Something was off, his gut seemed to say to him.

Trusting his instinct, he ordered everyone out of the building. Moments later, the structure collapsed. It was a miracle. Everyone was saved because the firefighter had a “bad feeling” and trusted that feeling.

This firefighter is far from the only expert to describe their abilities in supernatural terms. Terms like “spidey sense” and “sixth sense” often come up during interviews with experts. But NDM has developed interview techniques that are very proficient at uncovering what is going on in these scenarios.

In this particular case, as in all such cases, there was no ESP. The firefighter had noticed some anomalies—the fire’s heat level, loudness, and persistence didn’t match up with his subconscious expectations of what he thought he should feel and hear if he were right about the source of the fire, as he believed the fire to have originated in the kitchen.

But in this case, the fire was originating in a basement no one had told them about. Without realizing it, the firefighter’s brain picked up on discrepancies and sent a warning signal which he later interpreted to be ESP.

NDM’s emphasis on expertise and intuition has had a much stronger impact in Human Factors than in mainstream psychology. There are a few reasons for this:

Psychologists love lab studies. NDM doesn’t lend itself to tightly controlled experiments with college students. Instead, it relies on qualitative research and fieldwork—two things many psychologists consider four-letter words.

NDM is primarily an applied discipline. While psychologists often aim for generalizable theories, NDM is deeply practical. It cares about how people actually make decisions in real-world settings, even if that doesn’t lead to neat, publishable findings.

NDM is pro-intuition. Many psychologists—especially in the HB tradition—are deeply skeptical of intuition. HB research has shown time and time again that intuition is flawed. But NDM shows that expert intuition can lead to exceptional decisions. So which is it?

This perceived conflict led to a six-year-long adversarial collaboration between Klein and Kahneman, culminating in one of my favorite papers: “Conditions for Intuitive Expertise: A Failure to Disagree” (Yes, this substack is named after this paper).

Everyone wanted a dramatic showdown between these two giants of decision science, but instead, they found common ground. They agreed on the conditions under which intuition can be trusted:

Intuition is reliable in environments with valid cues and consistent feedback (like firefighting or surgery).

Intuition is unreliable in environments where feedback is delayed or misleading (like stock trading or political forecasting).

Despite the subtitle, Kahneman and Klein still disagreed on a lot. Their biggest difference, however, was dispositional. Kahneman enjoyed studying human errors; Klein preferred studying successes. They admitted that this fundamental difference in disposition meant they would never fully reconcile their views, so they left the job of bridging the gap to future researchers.

My Take

I think NDM is going to win the Great Rationality Debate. Which is why, naturally, I now work for Gary Klein.

The RPD model shows that real-world decision-making isn’t just a series of isolated heuristics—it’s about dynamically chaining heuristics together in ways far more sophisticated than HB or FF accounts suggest—what we call macrocognition. And the Data-Frame Theory gets to the heart of what I think it means to be rational.

Ultimately, I believe studying experts in the field gives us a much clearer picture of decision-making than studying heuristics and errors in a lab. But of course, that’s my bias.

My only complaint is that NDM is still divorced from the other literatures, and hasn’t done enough to understand the microcognitive heuristics and processes that underlie their models. But I can hardly blame them. Who cares about understanding the statistical underpinnings of intuition when you can instead interview firefighters, fighter pilots, and Law Enforcement about their spidey sense? The applied stuff is where NDM is most interesting.

Conclusion

Should these schools of thought reconcile into one unified discipline? I’m not sure. Each has its strengths, and I worry about what might be lost in the process.

Maybe instead of seeing them as competing theories striving for comprehensiveness, we should think of them as tools, each illuminating different aspects of decision-making. HB and FF uncover heuristics—HB explains when they go wrong, and FF explains when they go right, while NDM shows what happens when heuristics are chained together by experts into larger macrocognitive processes like Recognition-Primed Decision Making (RPD). Meanwhile CDM explains what to do in certain types of well-defined problems.

Under this definition, they are less different paradigms than they are different communities. The differences we see might not be fundamental, but instead may be differences in the types of questions asked, and in rhetorical flourishes researchers use when describing the importance of their work.

But while I worry we might dilute their ability to do these tasks well if we forced them into a single “master” research paradigm, I do want a comprehensive understanding of decision-making. And it seems like for this to happen, some sort of reconciliation needs to happen. We need to resolve some of the sources of disagreement that are more than just rhetoric.

And I do think that paradigm is beginning to emerge. A second Great Rationality Debate seems to be emerging, driven by a new school of thought called Generative Rationality. This school critiques both HB and FF on some of their foundational assumptions, and I think finds common ground with the Data-Frame Theory of Sensemaking of NDM.

At the same time, HB is undergoing what some call a “cognitive turn”, shifting its focus towards a more nuanced understanding of cognition. One particular theory they have developed is, in my mind, a more math-y version of RPD—the foundational theory in NDM.

These movements suggest that, whether by design or necessity, the different schools may soon find themselves speaking the same language again. Perhaps if we stop focusing on the yay/boo debate around human rationality and instead focus on the actual cognition, we’ll find surprising similarities.

I hope this reconciliation happens. It’s a big part of the reason I named this Substack what I have named it. I think before long, the various camps will learn how to talk to each other again, and I want to be a part of that reconciliation.

Even Kahneman, before he passed, seemed to sense a shift coming in the field.8

“I expect everything that I have done to be overwritten. It’s nothing of eternal value. I am surprised that the work that Amos and I did has survived for half a century. That’s remarkable. It’s like an athletic achievement. But it’s going to be overwritten. I am seeing that happen. I am old enough and seeing the beginnings of the overwriting. The future is going to be different. There is going to be, it seems in psychology, a return to rationality.”

I, too, see writing on the wall. But with his characteristic pessimism9, I think Kahneman has misread. What is coming is not an over-writing, but a bridge which unites the traditions on common cognitive foundation.

Or at least, that is what I am working towards.

To the true nerds,

Below I am including a lot bunch of books, articles, and podcasts that I enjoyed, or which have been influential on me. With two exceptions I plan to rectify later this year, I have read (or listened to) every source here. But that doesn’t mean my memory is perfect, and my descriptions may contain errors. Forgive me for any mistakes.

I am also not including any sources that talk about Classical Decision-Making for the simple reason that I have not read very many sources that are explicitly about those mathematical models, as most of what I know about them is through critiques and by understanding how heuristics are biased from them.

Note also that I am intentionally trying to include sources that talk about how these schools of thought talk to each other. In such cases where more than one school of thought is talked about, the label I put them under is fairly arbitrary.

Understanding Heuristics and Biases (HB)

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman – The bestselling book explaining HB.

The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds by Michael Lewis – A more engaging account of the personal story behind HB.

Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters by Steven Pinker – The most up-to-date overview of HB.

They Thought We Were Ridiculous by Behavioral Grooves and Opinion Science Podcast – A podcast series detailing the history of Behavioral Economics and HB.

Ending the Rationality Wars: How to Make Disputes About Human Rationality Disappear by Richard Samuels, Stephen Stich, Michael Bishop – on where HB and FF agree, and where they do not

Understanding Fast and Frugal (FF)

Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart by Gerd Gigerenzer, Peter Todd, and the ABC Research Group – The foundational book on FF.

Optimally Irrational: The Good Reasons We Behave the Way We Do by Lionel Page – A modern take on FF with economic insights.

How to Make Cognitive Illusions Disappear: Beyond “Heuristics and Biases” by Gerd Gigerenzer – a foundational paper critiquing HB

The Rationality Wars: A Personal Reflection by Gerd Gigerenzer – A good overview of the history of decision-making from the perspective of Gigerenzer

Expert Intuition Is Not Rational Choice by Gerd Gigerenzer – A review by Gigerenzer of Klein’s book Sources of Power

The Great Rationality Debate by Phillip Tetlock and Barb Mellers — An article explaining some of the history of the debate between FF and HB

Understanding Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM)

Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions by Gary Klein – The foundational text on NDM.

Naturalistic Decision-Making Association – A hub for NDM research and applications.

NDM Podcast hosted by Brian Moon and Laura Militello – A great resource for discussions on NDM.

Conditions for Intuitive Expertise: A Failure to Disagree by Daniel Kahneman and Gary Klein – An adversarial collaboration between Klein and Kahneman on when intuition can be trusted

A Naturalistic Decision-Making Perspective on Studying Intuitive Decision Making by Gary Klein – Recommendations from Gary Klein to FF and HB researchers

Can You Have Effective Decision Making without Expertise? by Gary Klein – A review by Klein of Gigerenzer’s book Simply Rational

Understanding Generative Rationality (GR)

(Not covered in detail in this essay, but those who are curious about where I see the field going may be interested.)

The Fallacy of Obviousness by Teppo Felin – a popular write-up of a critique of HB and FF

Mind, Rationality, and Cognition: An Interdisciplinary Debate by…lots of people. – A back and forth between titans of the field

A Generative View of Rationality and Growing Awareness by Teppo Felin, Jan Koenderink, and Joachim Krueger – An explanation of Generative Rationality

Rationality and Relevance Realization by Anna Riedl and John Vervaeke – An article making similar arguments that has been highly influential on me

Apologies to Organizational Decision-Making (ODM), Managerial Decision-Making (MDM), Generative Rationality (GR), and whatever other acronym I might have missed, for not including you as a major school of thought. I either don’t know enough about you, or I struggled to write about you in a compelling way.

The Great Rationality Debate is sometimes depicted as only between FF and HB. But I think that is a narrow view.

5 cents (Most people instinctively say 10 cents). 5 minutes (Most say 100 minutes). 47 days (Most say 24 days).

Sometimes Heuristics and Biases is also wrapped up into Behavioral Economics, Judgment and Decision-Making (JDM), and Behavioral Decision-Theory (BDT) in case you wanted more acronyms.

There is also non systematic errors called “noise.” Kahneman had always discounted the importance of noise earlier in his career. But he eventually came around to realize it was also very important and wrote a spiritual sequel to Thinking Fast and Slow called Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment. It’s a tough read. If you are interested, read a summary.

Jonathon Baron presents a similar table in his excellent textbook about HB called Thinking and Deciding.

If you google ‘hate the word irrational Kahneman’, you’ll find a few sources where he has talked about his loathing of the word. When Kahneman uses the word “rational” he is referring to Rational Choice Theory and CDM, not the layperson definition.

h/t to Lionel Page for introducing me to this quote in his essay on Why we should look for the good reasons behind our behaviour

Kahneman is so pessimistic that it is hurtful to listen to him sometimes. Kahneman is one of the greats. Eternity is a long time and isn’t the standard we should hold researchers to.

It obviously depends on context. Heuristics are cheap and dirty tools that are amazing in situations of short timescales. When you have more time it can often make sense to apply full blown cost benefit analysis. By careful cost benefit analysis I have decided to decide most things just based on vibes. You could call this strategy 'metarationality' if you define rationality to mean the formal logical stuff. If you define rationality more sanely you'd find no contradiction between the different schools of thought. They all have different roles in decision making

Great overview. I'll come back to this as it's such a good balance between summary and detail. It strikes me that a key piece would be whether or how NDM might 'scale' into areas where experience might not exist or where fast feedback isnt realistic/ possible.

Also, a question: where do concepts like belief-based utility tie into these various models? During my masters, I grew quite fond of the idea that our beliefs are similar to possessions, and we struggle to simply discard them in decision making. It seems like a fusion across #1 and #2.