Rethinking the Edges of the Mind – Part I

What is context? Why is it so hard to study? Can we redraw the boundaries of psychology so that context becomes content?

I. The non-arbitrary boundaries of scientific disciplines

“Why did the chicken cross the road?” isn’t usually a very deep question. But in Behave, Robert Sapolsky uses it as a jumping off point to expand on causality and the boundaries of scientific disciplines.

He walks through various possible explanations of the chicken’s behavior: a psychoneuroendocrinologist says its due to estrogen levels, as there is a sexy rooster on the other side; a bioengineer instead describes the mechanics of chicken legs; and the evolutionary biologist explains it in terms of mating behavior and selection pressures.

Each explanation is valid and correct, but also none is complete on its own. Sapolsky’s point is that siloed thinking will prevent you from fully understanding the behavior. Just because your job is to study hormones doesn’t mean you get to ignore culture, cognition, evolution, or anything else that might be relevant.

I’ve always loved Sapolsky’s build on this classic joke as a reminder that science operates through these overlapping but partial perspectives. Each discipline stacks like lenses in a microscope: from cells to circuits to cognition to culture, each lens brings a different layer into focus. No single frame captures everything, but together, they give us a more detailed picture than we otherwise could have gotten.

But while interdisciplinarity is necessary for a complete understanding of pollo locomotion, that does not mean we should collapse disciplines. Estrogen and culture are different kinds of things, and so require different tools and methodologies. So while the disciplines are arbitrary in one sense, in another they are also reflections of genuine differences. You can’t study cultural narratives with a syringe.

Besides this ontological (and therefore methodological) reason for the divide between disciplines, there is also an epistemological one; focus. Each discipline—as well as every model and theory—ignores the rest of the world, not out of ignorance, but because of the impossibility of bringing everything into focus at once. Each discipline, model, and theory has a blind spot where there exists the entire rest of the world, and these blind spots are features, not bugs. The blind spots are what afford us the ability to zero in on the part of the world we are most interested in.

This intentional ignorance is actually where science gets its power. The common saying is that all models are wrong, but that statement can be misleading. In truth, all models are intentionally wrong. They deliberately bracket out most of the world so that we can focus on some small part of it. Science advances not despite blind spots, but because of them. The ability to be temporarily ignorant of the rest of the universe is the goal of good science.1

This can seem paradoxical, but it is quite common sense when you think it through. Each discipline is defined by both a boundary and a lens. The boundary is what brackets out most of the world as "not relevant”, or as “something to be controlled”, and so therefore acts like a dam holding back a flood of all the possible things we could focus on. The lens, on the other hand, is what brings the particular relevant aspect of the world into sharp focus, be it neurons, narratives, or natural selection.

We need both: lenses to reveal, and boundaries to isolate. The boundaries prevent distraction and dilution; the lenses help us detect detail and structure. Together, they allow science to temporarily ignore the complexity of the whole in order to understand a part. Because if a psychoneuroendocrinologist had to account for bioengineering and evolution every time they ran a study, they’d never get anything done.

The two questions I wish to ask in this essay are the following: has psychology placed its boundaries in the right place? And does it have the right lens?

II. Context is that which leaks in. But sometimes it floods.

Disciplinary boundaries are necessary, but they are also leaky. Causal forces from other levels of analysis leak in through the edges. And worse, because they’re from a different level of analysis, we don’t have the right lens to bring them into focus. The evolutionary psychologist is not a cultural psychologist, and so will have a hard time bringing specific cultural practices into focus when they don’t fit in with the clean evolutionary model. As a result, culture is always getting in the way of their true subject of study.

This leaking in from a different level of analysis is what we call context. Context isn’t part of the model—that we call content—instead it’s what the model left outside the boundaries, but is leaking back in anyways. It is the residual interference we failed to bracket out. An interdisciplinary leakage that our lens isn’t built to handle.

Of course, context isn’t a real thing out in the world. It is instead an artefact of how we draw our boundaries. Since the world doesn’t come pre-sliced, true isolation is impossible. If you could fully isolate a system so that there was no context or leakage, you’d isolate it from yourself too. You couldn’t observe it at all. Context is therefore inherent to science. The inevitable byproduct of having scientific disciplines and scientific models which attempt to isolate and focus on one small aspect of reality.2

But while some context leaking in is ok and inevitable, it can sometimes become too much. Less a drip, and more a deluge. Our subject of study is so context sensitive to the leaking that the subject just doesn’t sit still long enough for us to get our bearings. It's like the dam has broke.

When this happens, we have to ask ourselves whether there might be something wrong with our boundaries. Perhaps the issue is not that we are unsure how to control for context and isolate it, but rather, maybe what we wanted to dismiss as context is actually the content we should have focused on. Maybe we got the boundaries wrong. Maybe what we wrote off as noise was actually the signal, and our models are just underfit.

Or to put it more eloquently, maybe we built the dam in the wrong damn place.

Because while the boundaries around our models and between our disciplines serve a purpose, they’re still human-made. The world doesn’t actually care about the distinction between the content of our models and the context that leaks in—we invented that distinction when we put the dams up in the first place. The difference between content and context is pragmatic, not actual.

So now I ask again: has psychology placed its boundaries in the right place? And does it have the right lens?

Because it seems that psychology has some pretty systematic errors. The leaking of context into psychology is positively diluvian. Everywhere you go, you hear a magic phrase; context matters. A phrase that is a tacit acknowledgement that, in our attempt to bracket out the rest of the world and put some dam boundaries around our subject of study, there are gaps large enough for the world to leak back in and disrupt our focus. It’s a phrase that means that what we have left outside the dam boundaries is flooding back in making it difficult to study the thing we are interested in. A phrase that means the dam boundaries are not holding.

And after hearing ‘context matters’ so many times, I’ve started to wonder that maybe the problem isn’t the lack of rigorous controls of the context. Maybe instead, psychology is just systematically underfit. What we dismissed as noise is signal, our context to be controlled is actually content to be studied.

Maybe, that is to say, we put the dam in the wrong damn place.

III. Are all soft sciences just leaky sciences?

Of course, it isn’t necessarily the case that there are better boundaries. Psychology isn’t the only discipline with a major leak. As you move up levels of analysis—from atoms to cells to societies—there seems to be an inherent increase in leakiness. The boundaries blur, and things get messy.

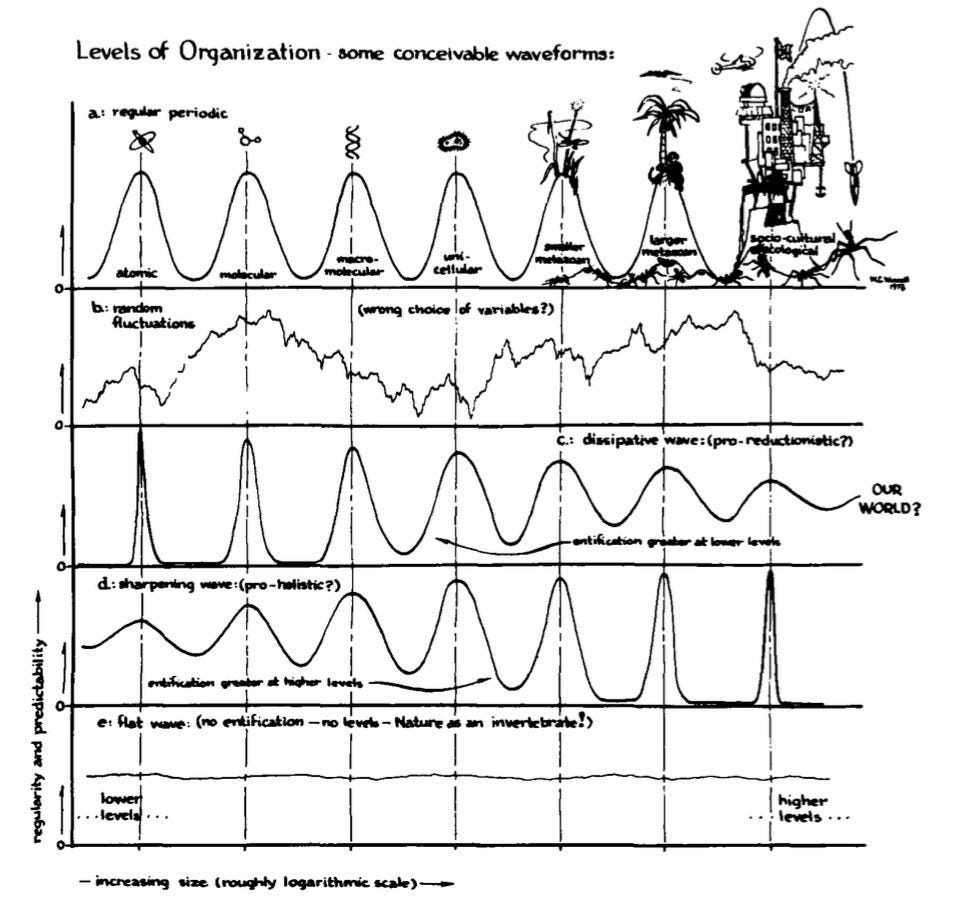

The philosopher William Wimsatt has this great series of five charts showing different ways the world could have been. The x-axis represents increasingly larger levels of analysis, and on the y-axis you have how regular and predictable the entities at that level of analysis are—or said differently, how context sensitive the entities are.

In the first chart, you’ve got a clean, predictable world where each level behaves as well as the one below. Sociology is as lawlike as physics. In the next chart, things fall apart—levels become unpredictable, disappear, and bleed into each other in a random walk. Then in the last two charts he imagines the world becoming less leaky at higher levels of analysis, or a world where distinct levels never emerge at all.

However, in Wimsatt’s third chart—the one that most resembles our reality—things get fuzzier as you move up levels. The edges get sloppier. By the time you reach society, the models are barely holding anything back. The dam boundaries are about as water tight as a cheese grater.

This is one way to understand the difference between the hard and soft sciences. In the hard sciences, like physics and chemistry, the units are more easily isolated, and so context doesn’t leak in and overwhelm the model. You can actually do math because the units of analysis are independent enough to behave according to the basic rules of arithmetic.

But in a soft science like sociology or anthropology, your units of analysis are not quite unitary. And building clean generalizable models of something which can be divided in so many ways, and influenced by so many things, means you'll always have some leakage. Mathematical models become increasingly inaccurate as the boundaries get leakier, and the discipline becomes increasingly context sensitive.

I think of soft science as like a science of raindrops on a window. Raindrops on a window are not mysterious. But if you draw your boundaries at the raindrop level of analysis, you may just lose your mind. A raindrop appears on the window, splatters into fragments, coalesces with others, then splits again. One raindrop plus one raindrop equals… one raindrop. But only until it doesn’t.

Raindrops are not clean, unitary objects, and they’re shaped by all kinds of interactions: surface tension, wind, temperature, the shape of the glass, etc.. You can’t model them with simple arithmetic. Instead, if you want to keep to the raindrop level of analysis, you have to settle for tendencies. You identify patterns, describe edge cases, use qualitative insight. In essence, you do soft science. It’s not that the raindrop level of analysis is wrong. Indeed, it may give you exactly what you need. But the level of analysis itself just doesn’t lend itself to hard science kinds of analyses.

And maybe that’s just the nature of all the social sciences, including psychology. The boundaries around neurons are crisp and clear, but the boundaries around psychological constructs are not. Psychological explanations just don’t hold steady the way chemical or cellular ones do.

Behavioral models likewise. Behavior bleeds into beliefs, which bleed into norms, which bleed into culture. The object of study won’t sit still because its very nature is to change, adapt, and interact.

So we conclude that, in psychology, the subject matter is simply too unstable, too context-sensitive to ever allow anything approaching hard science.

And I’m sympathetic to that conclusion. There is definitely some truth to it.

But I am also discontent, and I think you should be too. If the boundaries are arbitrary, then it is always possible we’ve drawn them in the wrong place. Maybe if we re-drew the boundaries, things would come into focus, and the leaking wouldn’t be as severe. Maybe we’re doing a science of raindrops at the raindrop level of analysis when we could be looking at weight or volume or something else entirely.

Psychology isn’t a healthy science, and maybe that is because we have the wrong damn boundaries.

IV. Dissatisfaction with leaky psychology

In Ethan Ludwin-Peery’s essay, Why Psychology Hasn’t Had a Big New Idea in Decades3, he proposes different ways to re-conceptualize psychology. He argues that instead of pure psychology we might need to study psychology + neuroscience, or psychology + economics, or do deep dives into memory, value, or even plants. Or perhaps none of the above. Whatever it is, he argues we need to re-conceptualize the very boundaries of psychology.

The reason he thinks such a re-conceptualization may be necessary is that he believes psychology is pre-paradigmatic. The comparison he makes is to alchemy.

Alchemists made measurements, ran experiments, and had causal theories. Sometimes they would even share their findings so that others could then replicate what they had found (though ambition often led them to stay silent about what they found). And at the end of the day, alchemists did in fact make many discoveries.

But was it science?

Alchemy was so conceptually confused that, despite many of the trappings of science, we are reluctant to grant it the title.

However, that's probably just gatekeeping. Bad science is still science. Ethan thinks the best term is ‘pre-paradigmatic’, which implies they were attempting science by proposing theories, testing hypotheses, and all the other things a scientist should do…but without a sufficient understanding of their subject to even agree on what it would mean to do good science.

One way to make this claim more intuitive is to recognize that alchemists didn’t even know what counted as a replication. Their categorization of the world was so confused that they had no clear sense of what variables to control for. When burning the egg of a newt to extract the essence of water, did the phase of the moon matter? The species of wood used to heat the fire? Whether the newt was pregnant? Lacking a framework to distinguish relevant from irrelevant factors (i.e., clear boundaries), their experiments were inherently ambiguous. If two alchemists got different results, they had no way of knowing why. Experimentation by itself is not enough—you need a paradigm to help make sense of it all.

Without a paradigm, for alchemists, it was not just that Ceteris Paribus was an unrealistic ideal, it was that they didn't even know what it would mean for all else to be equal. They didn’t actually know what was relevant. They didn’t have clear boundaries to tell them what kind of stuff they were interested in, or the right kind of lenses to bring that stuff into focus.

But then centuries passed, and humans learned a few things. Alchemy turned into chemistry. Not through an increase in methodological rigor, but by redefining what the subject of study even was. Earth, water, air, and fire turned out to be phases of matter, not the basic elements of reality themselves—and with this reconceptualization of the subject, a real paradigmatic science could emerge. One with a unifying framework that helped scientists to run controlled replicable experiments and have consistent interpretation of the results.

And the question is whether psychology is perhaps a bit more like alchemy than chemistry.

Of course, psychology isn’t quite as lost as alchemy. I think that is a tad too insulting. But it might still be pre-paradigmatic—or at least lacking a good paradigm. Scientific in method, but lacking the conceptual framework for full explanations and replications.

In mature sciences, claims come with relevant provisos. “Sugar dissolves in water” assumes you don’t freeze it instantly. “Vinegar and baking soda create a volcano effect” assumes you’re in earth-like conditions, and so it doesn’t count as a replication if you do it on Pluto. These provisos are an implicit part of the paradigm, left unstated simply because there are simply too many of them. But because an alchemist from Pluto does not understand the paradigm, the provisos would need to be spelled out so that they could verify the chemist’s claim experimentally.

But in psychology…

In psychology it is just assumed that provisos exist, and we don’t hold it against a theory if it happens to accidentally run afoul of one of them. After all, you can’t expect someone to define ALL the context, right?

Ceteris paribus in psychology, as it was in alchemy, doesn’t just fail as an ideal—we are unsure how to even define it. Our paradigm, such as it exists, is ambiguous about all the possible provisos.

This is why generalization has to be handled on a case-by-case basis. A good behavioral scientist never assumes a finding generalizes because all our theories are sometimes theories.

People are loss averse…sometimes. People obey authority figures…sometimes. Jared is agreeable…sometimes.

No psychological theory is as law-like as anything in chemistry because we don't know the provisos. Context leaks in, and we can’t cleanly isolate causes, or pin down universal mechanisms. Many of are most important findings are just glorified averages. (e.g., people tend to be Loss Averse)4

And maybe part of the reason for this unsatisfactory situation is that we’re stuck using categories as confused as earth, water, air, and fire—studying the phases of the elements of reality, but not the elements themselves. If we are not ever studying the right type of things, of course the models will fall apart. Of course we can't define the provisos, consistently replicate findings, or predict how things will generalize.5

If the dam boundaries are in the wrong damn place, of course there is going to be excessive leaking, and all we’ll be able to say is that “context matters.” Would not the alchemists have said the same when their own experiments didn’t replicate?

V. Pushing the boundaries to create a science of context

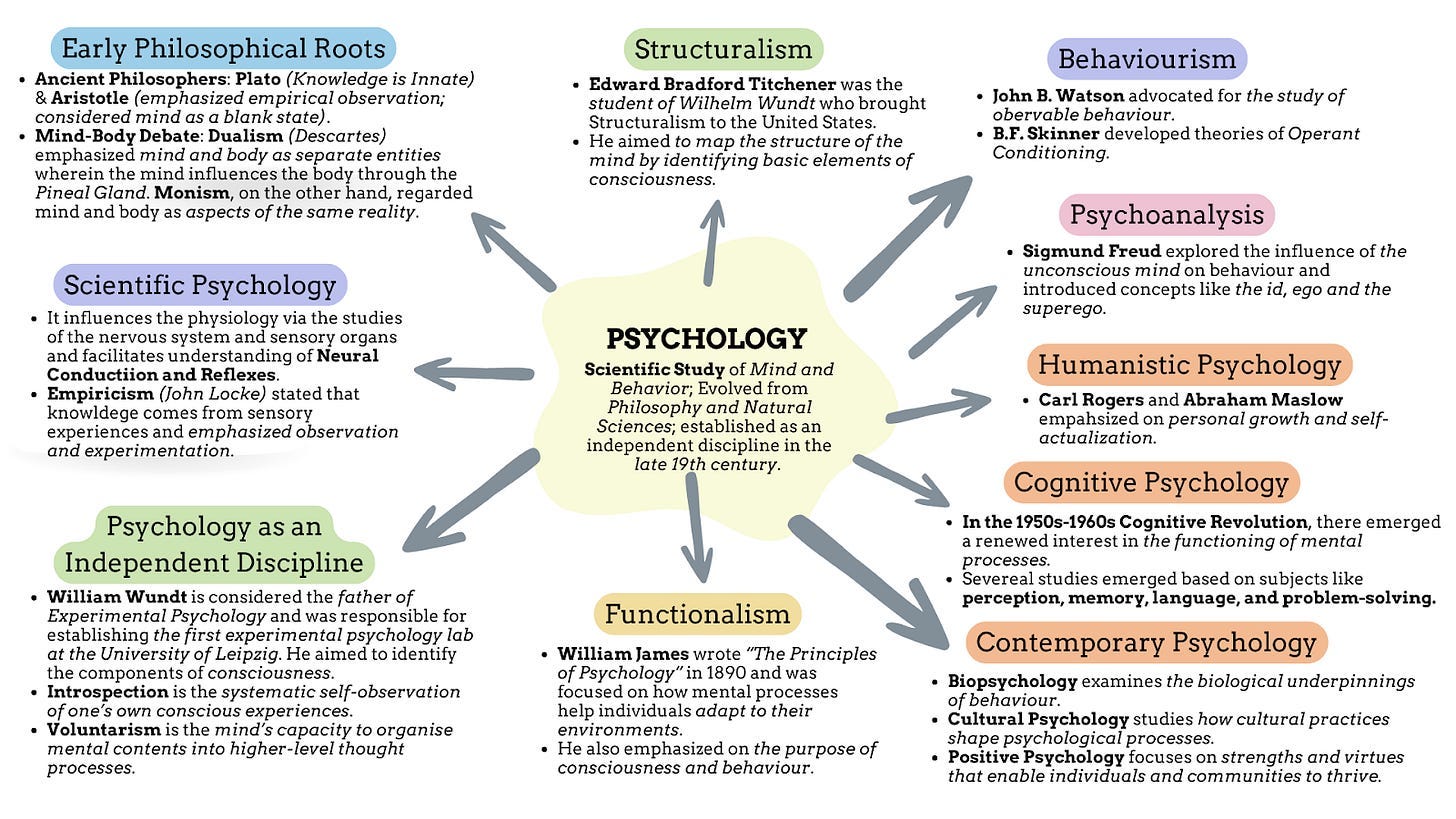

In psychology, our current level of analysis (the mind) was developed in the 60’s during the cognitive revolution. It is recent.

To be sure, the study of the mind persisted even through the dark days of behaviorism, and also in the decades and even centuries prior. But nevertheless, our current level of analysis wasn’t really formalized until relatively recently, and other boundaries have been drawn before and since, and may be drawn again.

The variety of possible boundaries, and how recent they are, is worth remembering. There may be something inevitable about the atomic, chemical, and cellular levels of analysis, but perhaps not for psychology. You'll notice that neither the mind or behavioral levels even make an appearance on Wimsatt’s chart about the five possible worlds. Those levels are different somehow.

And all this makes me wonder what would it take to redraw our boundaries? To move beyond endlessly repeating "context matters" without ever saying exactly what that context is? To build models that can replicate not by ignoring context, but by learning to incorporate it?

Maybe psychology’s leakiness is inevitable. Maybe, like Kevin Munger suggests, we need to abandon replication as the cornerstone of the social sciences.6 After all, if physicists struggle with modeling three bodies in space, why should psychologists—who study something far more multi-causal—expect to ever have anything less ambiguous “people tend to be loss averse”?

And yet, I can't shake the sense that psychology systematically underfits the complexity of human behavior by treating context as noise rather than structure. That our models leak not just because human behavior is messy, but because we drew our dam boundaries in the wrong damn place. Because if it changes behavior, then shouldn’t it be the very content that we study?

Perhaps the reason cognition and behavior don’t appear in Wimsatt’s chart is that they are not the result of compositional layering. Wimsatt’s chart shows levels that emerge by combining entities of the same kind: atoms into molecules, molecules into cells, cells into organisms, etc. Each level nests within the next, preserving ontological similarity.

But cognition isn’t built that way. It doesn’t arise from the stacking of like onto like. Instead, it emerges from the interaction between different kinds of things, namely, the organism and its environment.

Cognition, in this view, isn’t a “higher level” built atop the others. It’s a relational phenomenon—something that exists between levels rather than above them. That may be why it resists being plotted on the chart: it breaks the compositional metaphor that underlies it.

So I propose we push our boundaries outward. That we stop dismissing context as a nuisance, and start treating it as part of the object of study. That we build a science where context is no longer background noise, but foreground structure.

In an older essay I wrote that applied behavioral science is the science of context, since it doesn’t study psychological mechanisms, but how those functions work in specific contexts. But now I wonder why we would hold only applied psych to that standard? Maybe psychology as a whole needs to become a science of context. Or rather, perhaps psychology needs to redefine what it even considers to be content and context.

We don’t need to tear psychology down or insult it. There are areas that we understand pretty well, such as vision, habits, and others. Applied fields like Naturalistic Decision-Making show that even without perfect replication, we can create trainings based on psychological research which prepare people for life-and-death decisions. Psychology is not as hopeless as alchemy once was.

But for many of the questions we care most about, it feels like we are trying to build a science of raindrops.

In Part II, I’ll explore some of the most promising paths that I know of for turning context into content. I am not convinced that any definitively is the answer. But I am also not convinced any of them are not. So it is worth the effort to at least think them through.7

UPDATE:

Rethinking the Edges of the Mind - Part II

This is Part II of the series on context. In Part I, I argued that we have drawn the boundaries of psychology poorly, and that we need to incorporate context into the core subject of study. In this article, I present three ways we might do that. I will also include links to resources at the bottom.

The philosopher of causality Judea Pearl talks about how, absent a model, causality does not exist because “the manipulator and manipulated lose their distinction.” Causality, as we understand it, is a feature of our models, not of the universe.

Even Quantum Mechanics has context which leaks in. Observing particles involves interfering with them in ways that change their behavior. But that context was interesting enough to become content, and it is now taught in every class and textbook.

Ethan’s article was also recently published in Seeds of Science.

To be fair, Prospect Theory is more complicated than “people tend to be Loss Averse.” But it is often how the finding is summarized, and many other findings follow the same “tends to” formula.

Experimental History published a piece this morning that aligns quite a bit with how I think about the problems of psychology, even if I think the solution leaves something to be desired. Link here.

Though see Paul Blooms defense of replication.

If you have suggestions for what I should cover in Part II, let me know. I am still in the process of writing.

Great piece. I often consider that “context” is similar to the time-space relativity of mass and gravity. Subjectivity is intensely complex.

Good read, Jared, thanks! I wonder if we're at another inflection point when it comes to context in the history of psychology. Now of course I wasn't there to witness it but I can imagine Walter Mischel's argument caused similar ripples in psychology's identity back in the day. Instead of some person's innate quality (in his case it was personality he argued against, but we can stretch it to any other psychological construct), it's the person x situation interaction that let's behavior and psychological phenomena emerge. Now of course this is super simplified but what I do like is that it makes the tacit, explicit. There is a philosophical lens - scientific realism - that I believe skirts the boundary well, but I've no clue how - or even if - it's applied in psychology at all. Maybe worth investigating!