Rethinking the Edges of the Mind - Part II

Three different accounts of the nature of context; objective, subjective, & relational

This is Part II of the series on context. In Part I, I argued that we have drawn the boundaries of psychology poorly, and that we need to incorporate context into the core subject of study. In this article, I present three ways we might do that. I will also include links to resources at the bottom.

What makes humans distinct from all the other animals in the animal kingdoms is that we are the most flexible. Not physically—that distinction probably goes to our liquid feline friends—but in how we adapt to any environment. We are not blank slates, but we’re the most blank slate of any animal. Other animals are not deterministic, but they’re more deterministic.

This flexibility and adaptivity is made possible because of our ability to take advantage of our context. Humans don’t ignore the environment, nor are we merely resilient to it. Instead, we integrate it into everything we do.

This is great news for humans. But it is also terrible news for psychologists. How do you study something as adaptive, and therefore as context-sensitive, as humans?

In Part I, I argued that what we have left something out of our study of psychology—namely context. And this context is flooding back in and disrupting our field. I further argued that if we want to develop a truly paradigmatic psychology with robust theory capable of replication and generalization, we need to expand the boundaries of our discipline and stop treating context as something separate from the subject we study, but as core to it.

Consider physics. A physicist might run an experiment on how billiard balls bounce off each other, and they will model this system using variables such as angles, weight, friction, force, etc. However, in that model, the physicists would probably not include a term for the gravitational pull of Jupiter. Sure, the gravitational pull is interfering with the experiment in some minuscule way (it is “leaking” in). But not enough to affect the results or invalidate the model. So they treat it as irrelevant context.

But keep in mind, the gravitational influence of Jupiter is still the type of thing physicists study. They might ignore it in a given experiment, but that is a temporary disinterest, not a declaration of irrelevance. When the gravity of Jupiter becomes significant, physics has theories to account for it. It is still physics.

I argue psychological context should work the same way. If something influences human cognition and behavior, then it should be the type of thing psychologists study. We might ignore it temporarily within a particular study or subdiscipline, but that shouldn’t imply permanent disinterest. Our theories of context need to be just as strong as our theories of reasoning. Or better said: they should be so well-integrated that the distinction between a theory of context and a theory of psychology starts to disappear.

But what would that actually look like?

I have no sure answers. Instead, I’ll outline three different ways we could think about the problem of context, not as an exhaustive list of possibilities, but as an exploration of what I consider most promising. Each of these approaches reflects a fundamentally different theory of what context even is:

Context as external and measurable

Context as subjective interpretation

Context as relational and co-constituted

Context cartography: the brute force approach

It is worth starting with Cartography because it is in some ways the simplest of the three approaches. The idea is this: exhaustively map every potentially relevant factor so that we understand how studies relate to each other in context-space.

The problem, it is argued, is that psychological research isn’t commensurable—our studies are not apples to apples comparisons. Research articles don’t explicitly mention all the relevant variables, and they often use different terms for the same thing. The result is that our methodologies are so ill defined that it is impossible to tell whether one study is actually a replication of another or not. Tyler Cowen has a really great line about this.

“Every [Behavioral Economics] paper is this kind of little isolated universe, with its own model, with its own data set. They're kind of like…Leibniz Monads; you're not sure how they interact with other papers."

So what’s the solution?

The cartography approach says: brute-force it. Exhaustively log, track, and measure everything.

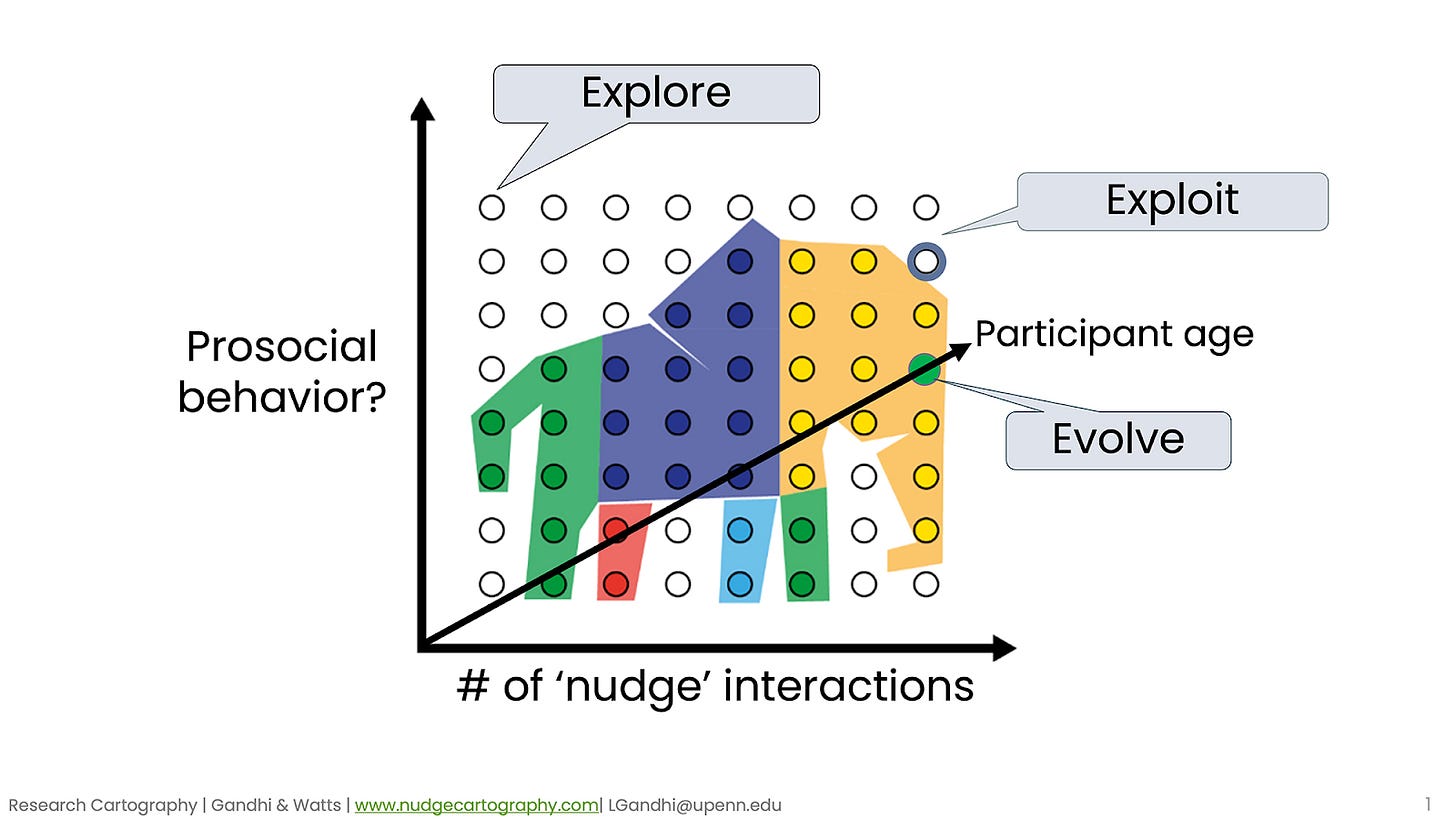

This is what Linnea Gandhi is doing at Wharton. In her research, she is building on Duncan Watts ideas on integrative experimentation to create what she calls Nudge Cartography; “As the name suggests, we aim to map studies of various nudges. This work will provide researchers and policymakers with a framework for finding the most effective nudges for a specific use case.”

Her team1 reads, re-reads, and re-re-reads hundreds of studies to exhaustively catalogue every potentially relevant factor. On their official website, they say they have analyzed 226 studies and identified 384 variables they think matter in those studies2. This lets them plot each study into a 384-dimensional space, mapping how interventions cluster, which dimensions matter, and what areas remain unexplored.

Nudge Cartography is the experimental methodology that I am most excited about within the traditional approach to Behavioral Science. Mega-studies3, the other major experimental methodology being developed at Wharton, while interesting, rarely are relevant to me. Their hyper-optimization approach reveals very little about human nature outside of that very specific context.

Nudge cartography aspires to fix that problem. Instead of 100 interventions in one ill-defined context (as per the mega-study), you get one intervention across many clearly defined contexts. This is an extremely valuable effort and I wish it were getting more buzz.

Of course, Nudge Cartography has some downsides. The principal one being how laborious it is. I have a lot of respect for the research assistants doing this work. Every time I talk with one of them, I have to ask, “How many variables are you up to now?” Making psychological science commensurable is an exhausting task. Does anyone really want to try and log 384 variables? And what happens when you discover a new variable that matters? You have to go back and re-read all those papers to see whether that variable is present. If a study doesn’t clarify whether it was present? You call the original researchers and ask.

For me, this is too demanding to be a scalable solution for the entire field. I also wish it were more cognitive (see next section). But I may be wrong about the impossibility of codifying so much context, and regardless, it may be the most important effort happening in Behavioral Science right now. I recommend following Linnea and her team closely. Even if it doesn’t become what she hopes, I think we will learn something valuable about context itself. And that makes it a valuable effort.

Modeling the modeler: context as interpretation, not terrain

In physics, when we want to understand how billiard balls bounce off each other, we model the system by specifying variables and writing equations. We know what matters, and how it matters.

But in psychology, we’re not modeling a well-defined system—we’re trying to understand how a person makes sense of the situation: what they notice, what they ignore, and what stories they construct. More poetically, we are modeling the modeler, we are mapping the mapmaker. “Context” isn’t the 384-dimensional terrain, but the subjective interpretation of that terrain.

Consider a study that works in India but fails in Brazil. The difference in replication isn’t because of the the geo-coordinates, the culture, or even the translation of the study intervention—at least none of these variables are directly causal. Rather it is how people interpret those features in the moment. The context isn't some list of objectively defined features, but the subjective interpretation of those features. So unless we model how people interpret that context, we’ll never understand why certain interventions don’t generalize.

The psychologist who, I believe, has most directly confronted this issue of interpretation is Walter Mischel in his work on personality. In many ways, Mischel reverses the causal arrow that many imagine when thinking about personality. Rather than saying a child is high on an aggression trait, and that is why they are aggressive to adults, Mischel says that the child’s consistent perception of adults as threatening leads to aggressive behavior. The aggression trait isn’t a causal force, but instead just a label we use to summarize the behavioral pattern that results from the child’s perception.

Mischel justifies this view by pointing out that a child’s aggression is situation specific. A child that is consistently aggressive to adults is not necessarily consistently aggressive to other children. In such a case, the child must perceive children as friendly, and adults as less so (understandable), and therefore we conclude the behavior is driven by perception, not a generic “trait.”

This critique led to the Cognitive Affective Processing System (CAPS) model, which explains behavior not through traits, but by showing that people consistently construe (interpret or frame) similar situations in similar terms. For example, a child that always assumes kids are friendly, and that adults are a threat.

This consistency in construing situations in similar terms allows for the creation of ‘if-then’ rules of behavior4, such that important environmental features (e.g., the presence of adults) operate like cues in a habit loop leading to consistent behavioral patterns we can label and describe as personality.

Kahneman called Mischel’s work a “scandal” because it exposed the inadequacy of the existing trait based models. Existing trait-based models must treat predictable deviations from averages not as something to be explained, but as an error to be explained away5. But according to Mischel, such variability is not an error, but part and parcel of personality. The child’s variability in aggression is their personality.

You may be more familiar with Mischel’s more famous experiments involving marshmallows. Somehow, our interpretation of these experiments has actually gotten worse over time. Today, people say the experiments showed personalities stability, but Mischel hated that interpretation. Mischel wasn’t testing traits—he was teaching skills.

In the experiment, the researchers were teaching the children skills for resisting temptation by having them re-frame the situation they were in (e.g., ‘Imagine a picture frame around the marshmallow and that it is just a picture of a marshmallow.’). Mischel believed these reframing skills, once learned, were something you could have for the rest of your life.6

CAPS is elegant, and (in my opinion) likely to be more accurate than the more traditional trait theory since it provides a causal account of personality. But it’s also more work for researchers. To understand how your subjects interpret the world, what they consider relevant, and why, you have to use methodologies more advanced than a survey. This is probably a major reason why CAPS never fully caught on: more accurate, less tractable. Modeling the modeler is a much more difficult task than estimating average behavior.

Still, we can learn from Mischel’s criticisms because they apply well beyond personality. Much of psychology, like the personality psychology Mischel was critiquing, is based on tendencies and averages. Prospect Theory claims people tend to be loss averse. The Bandwagon Effect describes what people tend to do. Even the debate about whether nudges “work” is really about averages. Indeed, our entire experimental and statistical paradigm is built around averages.

But a science built around averages becomes nearly unfalsifiable because you have a built-in escape valve. Averages aren’t theories or explanations, and certainly not a guarantee. They’re just summaries. They tell us what happened across a sample, not why or how. Psychologies reliance on averages is perhaps the thing most dissatisfying with our current approach to the study of the mind.

This is why I’m increasingly drawn to theories like CAPS, and Gary Klein’s Data-Frame Theory of Sensemaking which take framing seriously. It’s also why I like Cognitive Task Analysis which is a method for understanding what people noticed, when they noticed it, and how they made sense of it. It treats context and frames as core parts of cognition, not confounds to be controlled away.

Because it seems to me that if we could develop sufficient methodologies for understanding how people frame situations, that we might finally develop true causal accounts of behavior, understand what context is actually relevant in any experiment, and finally understand our problems with replication and generalization.

Transactional worldview: expanding the bounds of the mind

In the first installment of this series, I argued that we should extend the boundaries of the mind. But have we really done that so far? Perhaps these first two approaches do not go far enough, and we can get much more radical. Perhaps we can reconceive the mind itself. To think of it not as being located in the brain, but as a relationship between the brain, body, and environment.

This is hard to think about because we are so used to thinking of the brain as the seat of all cognition. But maybe trying to locate the mind in the brain is a category error, a vestige of our latent dualistic worldview. Rather than thinking of the mind as a thing with a location, we should instead think of it as a process or relationship between many moving parts—only some of which are neurons.

Is that too radical?

Maybe. So let’s scale it back to put everyone on more familiar ground. If you think of cognition as a type of information processing, then we should acknowledge that there is information processing in the tools we use, in how we shape our environments, how we position our bodies, etc.

This is the core of what I’ll call the Transactional Worldview: cognition doesn’t happen inside a brain or outside in the world, but rather arises in the dynamic coupling between the two. No central controller, but instead a series of tight feedback loops between brain, body, and world forming a system where meaning, action, and perception co-create each other to produce psychology main subject of study: cognition.

Some metaphors might help.

Think of a murmur of starlings in flight.

You cannot reduce the intelligence of the murmur of starlings to a single bird. Instead, to understand the collective intelligence of that moving mass, you have to understand how the birds interact with each other, with the wind, the predator birds they are avoiding, the ground, trees, etc. All the various interacting features of the system (living or not) contribute information to the entire system.

The idea is that perhaps cognition is a bit like the murmur. Rather than the information processing happening entirely in the brain as if a single controller was doing everything, perhaps much of the information processing is happening outside the brain, and is distributed in the environment such that intelligence is emergent from the brain-body-environment system.

This way of thinking is a central premise behind 4E cognition, an increasingly popular way to view the functioning of the brain. The titular E’s each push the boundaries of cognition outward:

Embodied: Our thinking is shaped by our bodily form, sensory systems, and physical interactions, and therefore our thoughts are not solely the product of abstract mental processes.

Embedded: Cognitive processes are shaped by and embedded within the physical, social, and cultural environment and the body's interactions with it.

Extended: Cognitive processes can be distributed into the environment through tools, external memory aids, and social interactions, which are all integral parts of the cognitive system existing beyond the skull.

Enactive: Cognition arises from the dynamic interaction between an organism and its environment.

These ideas are not necessarily dependent on each other, but in bundling them, the advocates of 4E cognition push the boundaries of the mind out as far as possible. Each of the E’s chips away at the traditional boundary between mind and world, and suggests that cognition isn’t in the brain, but is instead a relational phenomenon—a dynamic process enacted between brain, body, and environment.

4E Cognition has a rich intellectual history that I can’t do justice here. But I’ll mention one important intellectual predecessor which might help make it more intuitive.

Edwin Hutchins is the developer of a tradition called Distributed Cognition. In his work, he showed that a ship’s navigation isn’t in any one sailor’s head. No single sailor understood everything that was happening. Instead, the intelligence that was capable of navigation consisted in the coordination between charts, instruments, crew, and action. Without the entire system, navigation would fail.

The cognitive process itself extended across people, artefacts, and systems.

As I mentioned, each of the E’s has their own rich tradition and intellectual history, but this essay is dense enough without going into all of that. My aim isn’t to explain 4E, but to highlight the worldview they collectively suggest.

Personally, I see each of the 4 E’s, and their intellectual predecessors, as bugbears of traditional psychology. I have no idea how true any of them are, but they poke and prod and then nag at me to ask one very important question: how much of what we call cognition is actually done outside the brain? What if our perception of affordances doesn't result from cognition but instead precedes it? What role does the structure of the environment play in memory? Does any one sailor truly understand the navigation of the ship, or is navigation itself distributed throughout an entire process?

The Transactional Worldview suggests that context isn’t what surrounds cognition, but is instead part of what produces it. The environment isn’t a contaminant, but a co-author. Whether you want to take this literally or metaphorically is up to you. But I suspect that even as a metaphor, it may offer more explanatory power than many of psychology’s traditional constructs like traits, tendencies, and effects.

The takeaway for the Transactional Worldview is this; if we want to stop underfitting the context, we have to stop overfitting the brain. Behavior is not the output of internal mental machinery. It is the emergent property of a tightly coupled system. This is an idea worth taking seriously even if, like me, you are unsure how far to take the ideas.

Conclusion

So here we have three major approaches to rethinking the edges of the mind by treating context quite differently:

As external and measurable, which we can systematically map (Cartography).

As subjective and interpretive, shaped by how people construe situations (Modeling the Modeler).

As relational and co-constitutive, where cognition emerges through dynamic interaction (Transactional Worldview).

I don’t pretend this list is exhaustive, nor am I an expert in any of them. They are simply the approaches I have come across that seem to have the most bite. If you know of others, drop them below in the comments. Also, let me know which you find most plausible, as I suspect people will differ wildly on that account.

I also didn’t talk as much about methodology, ontology, or the nature of causality, each of which could fill another article. I may explore those issues in a future post depending on interest. In the meantime, I’ve included resources below for each of the three approaches, as well as other work that shaped how I think about context.

Resources

Nudge Cartography

Research Cartography: How to Build a Map to Navigate the “Do Nudges Work?” Debate and Beyond by Linnea Gandhi. A talk on Nudge Cartography.

Beyond playing 20 questions with nature: Integrative experiment design in the social and behavioral sciences by Almaatouq et al. One of the major inspirations for the Nudge Cartography.

Modeling the modeler

A Cognitive-Affective System Theory of Personality: Reconceptualizing Situations, Dispositions, Dynamics, and Invariance in Personality Structure by Mischel and Shoda. Describes their CAPS theory of personality.

Daniel Kahneman interviews Walter Mischel - I think the full interview is floating around somewhere, but I couldn’t find it before this went live

Data-Frame Theory of Sensemaking by Gary Klein. His take on how we develop frames. Very influential on me.

Use of the Critical Decision Method to elicit expert knowledge: A case study in the methodology of cognitive task analysis By Hoffman et al. The major interview technique used in Naturalistic Decision-Making

Transactional Worldview

4E Cognitive Science. A Brief overview.

Ecological. A brief overview (let me know if you know of a better overview)

Distributed Cognition by The Decision Lab. I was very pleasantly surprised they had this!

Foundations of an Ecological Approach to Psychology by Harry Heft. I took the term “Transactional Worldview” from here.

Externalism. A closely related term.

Other things which have shaped how I think about context

Context reconsidered: Complex signal ensembles, relational meaning, and population thinking in psychological science by Lisa Feldman Barrett. A very good paper arguing against mechanistic approaches to psychology.

Context Changes Everything: How Constraints Create Coherence by Alicia Juarrero. Fascinating, but hard to read.

Process Philosophy. I wish I was better at thinking in terms of processes than objects!

The company I was at shared interns with Linnea for a summer, and since I oversaw those interns, I was occasionally involved in conversations about Nudge Cartography. But I was only involved enough to feel comfortable bragging about it on Substack, and not enough to put it on my resume.

As of the last time they updated their webpage.

I was also involved in one of the mega-studies. They locked me in a windowless room where I cleaned data for a few hours everyday. As far as I know, they never used that “clean” data. I was also involved in a few conceptual conversations, but I don’t think I actually contributed anything. Nevertheless, it is on my resume.

Researchers in the Naturalistic Decision-Making have found this same “if-then” phenomenon. Experts form action rules based on consistent pattern recognition. See Recognition Primed Decision-making (RPD).

I think Kahneman likely saw Mischel’s critics in a similar light to his own critics; trying to explain away systematic deviations as if they were unimportant.

I don’t know whether Mischel truly believed that imagining a frame around a marshmallow was a big enough intervention that it would have a significant life impact many years later. But research does suggest that conscientiousness is associated with such re-framing abilities (an idea which I take very seriously despite my skepticism of trait based approaches).

"if we want to stop underfitting the context, we have to stop overfitting the brain." Great line, love this! Maybe also, stop overfitting the environment, since the traditional externalized view not only ignores relational interactions and transactions, but puts the burden fully on external variables (384 and counting, many conceptualized as outside the body) to do the heavy lifting.

It seems like there's an additional layer of context, in the sense of knowing when and where something becomes relevant context (i.e. the context for knowing which auxiliary assumption applies). What would it mean to study Jupiter's gravitation not as an object that happens to later get referenced as a contextual factor, but explicitly the conditions under which it becomes relevant *as* context for different things? Perhaps this question is incoherent or impossible. In any case, the appeal of the traditional external variables approach (including Cartography) is that breaking down everything into these little variables at least makes it easier to pick out particular sources of influence, however incomplete - whereas with the subjective and transactional frames it gets a lot more slippery and/or holistic. I suspect we need all three approaches, and more.

Thanks as always for expanding my mind and my models. I'm definitely looking more into nudge cartography and 4E cognition.