What is Naturalistic Decision-Making?

A brief overview of the field that convinced me biases don't matter

The origins of Naturalistic Decision-Making

In 1985, the US military was trying to understand how to train decision-making when they kept running into an little snafu; the literature on the topic was useless for their domain.

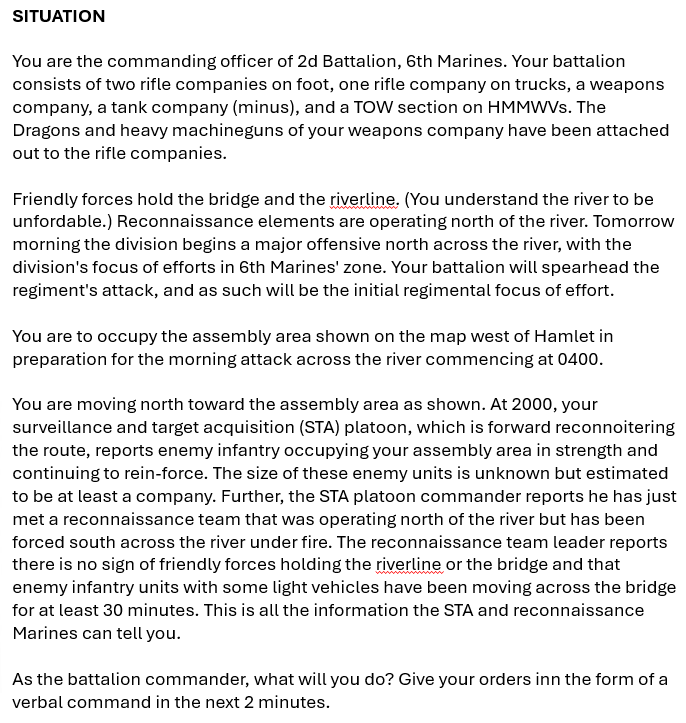

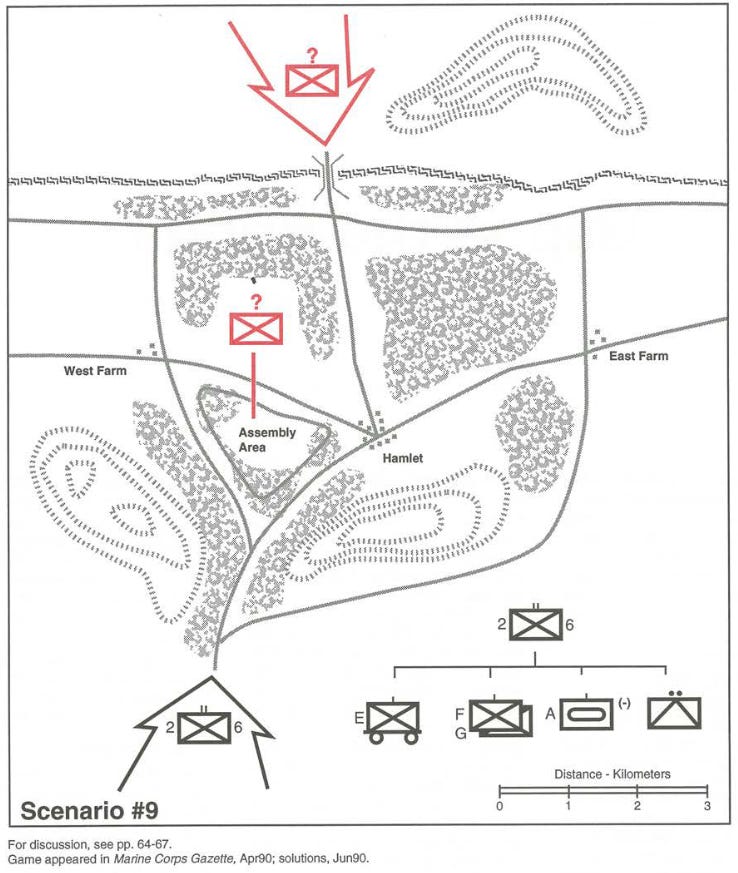

Imagine you are in a complicated battlefield situation, and you have to use Bayesian Decision Theory to calculate the best course of action in the next 2 minutes. Good luck!

Based on experience (and also a bit of common sense) the military concluded that real-world decision-making couldn’t work like the slow and cognitively taxing theories that were so popular in academia. But the alternative wasn’t clear either. If great generals and tacticians weren’t using these rational models, how were they still making such high quality decisions under extreme uncertainty and time pressure?

To figure this out, the Army decided to fund various researchers to study decision-making in quick paced and highly uncertain domains. One of the teams that won the contract was led by Gary Klein1.

Klein’s team knew they wanted to study real world experts in real world conditions outside of the lab. Since tagging along with the army on the battlefield was out of the question, the team turned to firefighters who they identified as perfect subjects. Not only were firefighters going to be experts in quick decision-making, they also had the advantage of lots of down time at the station between the fires when they could be interviewed.

But during the very first interview with a firefighter, not even a real interview but a practice one, they ran into their own little snafu. Klein recounts the conversation:

I said, "We're here to study how you make decisions, tough decisions."

He looked at me, and there was a certain look of not exactly contempt, but sort of condescension, I would say at least, and he said, "I've been a firefighter for 16 years now. I've been a captain, commander for 12 years, and all that time I can't think of a single decision I ever made."

"What?"

"I don't remember ever making a decision."

"How can that be? How do you know what to do?"

"It's just procedures, you just follow the procedures."

My heart sank, because we had just gotten the funding to do this study, and this guy is telling me they never make decisions. So right off the bat we were in big trouble. Before I finished with him, before I walked out, I asked him, "Can I see the procedure manuals?"

Because I figured maybe there's something in the procedure manuals that I could use to give me an idea of where to go next. He looked at me again with the same feeling of sort of condescension, (obviously I didn't know that much about their work) and he said,

"It's not written down. You just know."

There are many moments one could choose as the birth of Naturalistic Decision-Making, but I would nominate this conversation. It was one of the first major insights into how experts make decisions in naturalistic settings; to them, it doesn’t feel like a decision at all.

Klein’s team had assumed firefighting would be so quick paced that firefighters would deliberate between only 2-3 options at most. But instead they found they didn’t deliberate between any. Which isn’t to say what they did was easy, as they still regularly ran into situations where they didn’t know what to do. But the “generate and compare options” paradigm that academia taught wasn’t how real world decision-making happened.

Around the same time, other researchers in similarly high stake domains were discovering the same thing. In 1989, these researchers gathered in Dayton, Ohio not realizing what they were staring. At that first conference, they hadn’t yet conceptualized themselves as a distinct field of study, and they certainly didn’t have a name. But at that conference a few themes emerged

They were interested in complex, real-world (naturalistic) environments characterized by time pressure, uncertainty, ill-defined goals, high personal stakes, and other intricacies. Fields like firefighting, law enforcement, tactical decision-making, medicine, aerospace, etc.

They were interested in experienced experts who consistently performed well despite complexity. Not novices, and certainly not undergrads.

How people made sense of situations often mattered more than deliberating over predefined options.

The third theme stands out a little. While the first two themes identify similarities in what and who they studied, the third was more an insight that many of them had independently discovered, and which Klein had started to pull the string on in that initial practice interview with the fire commander.

Later, the field was christened Naturalistic Decision-Making (NDM). That Dayton meeting was just the first of many2.

How to make a decision without deciding

It wasn’t just that one fire commander who didn’t make decisions; they all said it. The researchers shifted tactics, asking about “tough cases” just to get away from the word. Later this approach of asking about tough cases got systemized into the Cognitive Task Analysis (CTA) method which we still use today.

What this proto-CTA helped reveal was that when the firefighters insisted they didn't make decisions, what they meant was that they were not deliberating between options. Instead, the situation itself implied what to do.

Consider a fictional Search-and-Rescue story:

A hiker goes missing. The SAR team assumes he took a wrong turn, so they work the junctions on the trail with dogs. Nothing.

Next theory: he went off trail for a shortcut. They search for broken branches and footprints on the edges of the trail, but nothing.

They start to wonder if he was ever on the trail in the first place. But then his mother says something interesting, “I don’t understand how he got lost—he had a new GPS watch. We tested it just the other day.”

Suddenly it clicks. He was probably testing his new watch. They change their search pattern to look for likely straight-line routes between the start and end points. That is where they find him, stuck in a ditch.

What I like about this story is that each theory implies how to search: wrong turn → check junctions; shortcut → check trail edges; direct navigation → follow straight lines. The challenge isn’t figuring out which search technique to use. That is always obvious because how he got lost implies the way to search. Instead, the difficulty is in understanding how he got lost in the first place. In other words, and to paraphrase that third theme, the ways in which the SAR team made sense of how the hiker got lost exerted greater influence on their actions than did deliberation over a set of predefined options.

While I do not want to diminish the expertise of SAR teams, I use that domain as an example because it is intuitive to even non-experts. There is an “if X, then Y” relationship between the situation and the action to take. Of course, in many complex domains the relationship between “X” and “Y” is much less obvious. And even knowing the right questions and actions to take to figure out which “X” situation you are in requires quite a bit of experience. But that is why it feels like protocol, not decision-making.

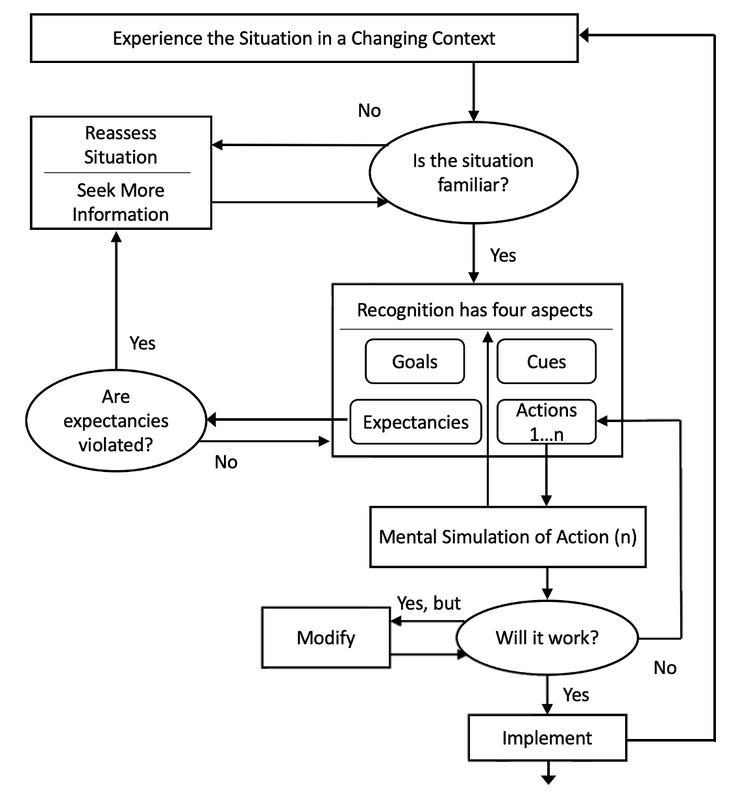

Klein’s team formalized this in the Recognition-Primed Decision (RPD) model which explains how recognition of the situation primes the appropriate action. The RPD model has become the dominant way to understand decision-making among experts across every highly uncertain and quick paced domain you can think of. If you want to know more, you can read my essay on the RPD model here, or the original (updated) article here.

Flawed intuitions

Kahneman and Tversky may be more familiar names than Klein, and readers may notice a tension between these thinkers. And indeed there is. The Heuristics and Biases (HB) programme that Kahneman and Tversky founded was based on the idea that intuition is riddled with systemic errors that they called biases. These biases are so persistent that Kahneman doubted they could be mitigated, and he instead preferred to replace humans with algorithms where possible.

As you may imagine, this is the exact opposite of Klein who is fascinated by stories of experts doing amazing things. Consider a famous story that Klein likes to recount.

During an interview, a firefighter claimed his ESP had saved his life and everyone in his crew. During the incident in question, they were in a burning house when he got a bad feeling. He ordered his crew out of the building, not knowing exactly why he gave the order. Moments later the building collapsed. Turns out the fire was in the basement which they hadn’t known about.

While impressive, it wasn’t anything paranormal. Klein was able to help the firefighter to recount various anomalies that he had identified during the course of the incident which had triggered the bad feeling; a fire that was too hot, too quiet, and not as responsive as it should be. It was this subconscious (System 1) anomaly detection which allowed him to intuit that his current understanding of the fire was insufficient. And since he knew better than to be inside a burning building where he didn’t fully understand the situation, he got a bad feeling about it3.

This is not the only incident where an expert in a domain came to believe they had ESP. Experts often struggle to explain what they do because so much of what they know and do is tacit. We have heard terms like sixth sense, spidey sense, or even magic as experts try to explain what they do. Mostly these terms are used tongue in cheek, but some do come to believe there is something mystical happening due to the difficulty of explaining their own tacit knowledge.

So how do we square this circle? How do we make sense of intuition that is so brilliant that it seems like magic, and at the same time make sense of intuition so flawed that finding those flaws led to Kahneman’s Nobel Prize? That was the question that Kahneman and Klein set out to solve when they decided to collaborate on a paper

Kahneman had long been an advocate of “adversarial collaborations” between researchers who disagreed. He has done a few over the years, but the one he did with Klein he described as his “most satisfying.” It took them 6 years to write their paper, and many hoped they would fail (such was and is the bad blood between the two fields). But fortunately for all of us, the two got along famously, and ended up writing “Conditions for intuitive expertise: a failure to disagree”. The very paper which inspired the name for this Substack.

Klein has actually always disliked the name of this paper because they actually disagreed quite a bit! But nevertheless, they did agree on some basic facts which they summarize at the end of their paper, and which I will try to summarize in one sentence;

Intuition starts flawed but can be trained to be adaptive in environments with high reliability and rapid feedback.

The reason Kahneman and Tversky found so many flaws is that they were focused on non-experts (undergrads) in novel domains (a lab experiment). In situations like that, the subjects don’t have time to develop expert intuition. Conversely, Klein’s subjects had decades of experience and training, and so their intuition was highly adapted to their domain.

Despite this ‘failure to disagree’, the fields to this day are in tension. NDM researchers believe the post-hoc analysis of biases so common among HB research can be extremely damaging as it often dismisses the very intuition that enables experts to succeed in the first place. Meanwhile, HB researchers view NDM with skepticism due to its emphasis on its qualitative methodologies, and its rejection of the more systematic approaches that HB tends to prescribe.

The two ended their article with an invitation that has yet to be fulfilled: “[Daniel Kahneman] is still fascinated by persistent errors, and [Gary Klein] still recoils when biases are mentioned. We hope, however, that our effort may help others do more than we have been able to do in bringing the insights of both communities to bear on their common subject.”

So what is expertise?

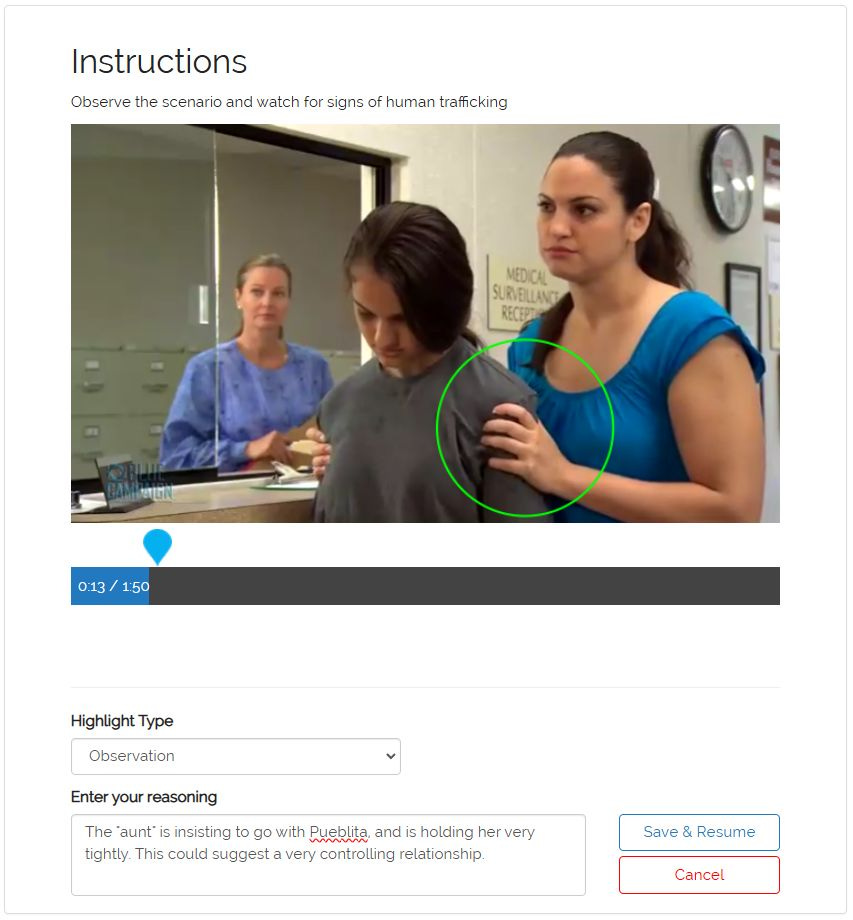

A common misperception is that expertise is just pattern matching and intuition (“System 1”). But that is too simple a story. A pattern that is relevant in one situation may not be relevant in another. The heat and loudness of the fire, the position of a rook relative to a castle, the way a victim carefully words what they say…these patterns are only relevant in certain contexts.

Another important thing to note is that even though it's not transferable, expertise is adaptive. What I mean by that is that expertise in, say, Chess, does not transfer to Go, but it does adapt to novel chess boards a grandmaster has never seen before. This also cannot be explained by a story of simple pattern matching.

I think of it this way; there is not a library of pre-existing patterns the expert is trying to match to, but instead, the expert’s mental model of the situation helps to generate patterns to look for. So the key to expertise is not primarily the pattern matching, but the effective mental models and mental simulation that allow the expert to predict what they should see, as well as to notice when things are not developing as they expected.

There is a bit of circularity here that is worth pointing out; the situational understanding shapes the patterns the expert looks for, but the patterns they notice shape their understanding. It seems like you can’t know what is relevant until you know what is happening, and you can’t know what is happening until you identify what is relevant. This relevance realization problem—knowing what matters before you know what’s happening, and vice versa—is, to me, the heart of expertise.

How do experts develop this ability? The easy answer is “through experience,” which is correct but incomplete. Sometimes someone with years of experience can still be a dunce. It has to be the type of experience that helps to build up one’s mental model of the situation. That requires an active mindset where they wrestle, think through, and predict, all while getting feedback—whether real or simulated. True experts are constantly pushing themselves in ways that others do not.

Conclusion

What I have covered here is rather paltry compared to the richness and depth of NDM. The field has covered so many fascinating domains, from astronauts, to fighter pilots, to Zen meditators. I said very little about CTA, and didn’t even mention some of the most important theories such as the Data-Frame Theory of Sensemaking and Macrocognition

But hopefully what I HAVE said is enough to at least intrigue those who are unfamiliar. I personally think NDM is the most important work happening with regard to how humans actually make decisions, and so it is important from both a theoretical and applied point of view. I wish more people would dig and discover its depths!

However, I have said a lot. So I will end with a final thought from Daniel Kahneman.

“Klein and I disagree on many things. In particular, I believe he is somewhat biased in favor of raw intuition, and he dislikes the very word "bias." But I am convinced that there should be more psychologists like him, and that the art and science of observing behavior should have a larger place in our thinking and in our curricula than it does at present.”

Disclaimer: Gary is one of my bosses at ShadowBox.

Join us next year in Charlottesville!

Or perhaps he recognized the signs of a fire burning underneath him? It is difficult to know exactly what he intuited.

As a surgeon i was taught "good decisions come from experience. Experience comes from bad decisions."

That sixth sense development is an iterative process.

Great article Jared - super interesting! Don't know if this has been said before, but this reminds me a lot of some ideas in heidegger: he essentially states that our skills result in the world 'disclosing itself' to us in certain ways, and that this disclosure then disposes us to act in certain ways. Seems like another subject that he was weirdly prescient on.